Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh

Recent articles published by local news sites in Bangladesh (Textile Today, Apparel Resources) report that a Ministry of Labour and Employment circular, issued on April 13th, permits garment exporting factories to have their employees work two more additional hours of overtime per day, for a possible legal total of four hours of overtime. The new overtime rule went into effect on April 17th and is set to remain in place for six months. This means that it is now legal for a factory to have its workers work 12 hours a day, 6 days a week, for a total of 72 hours per week. Before this circular was issued, the legal limit was 10 hours a day, for a total 60 hours a week.

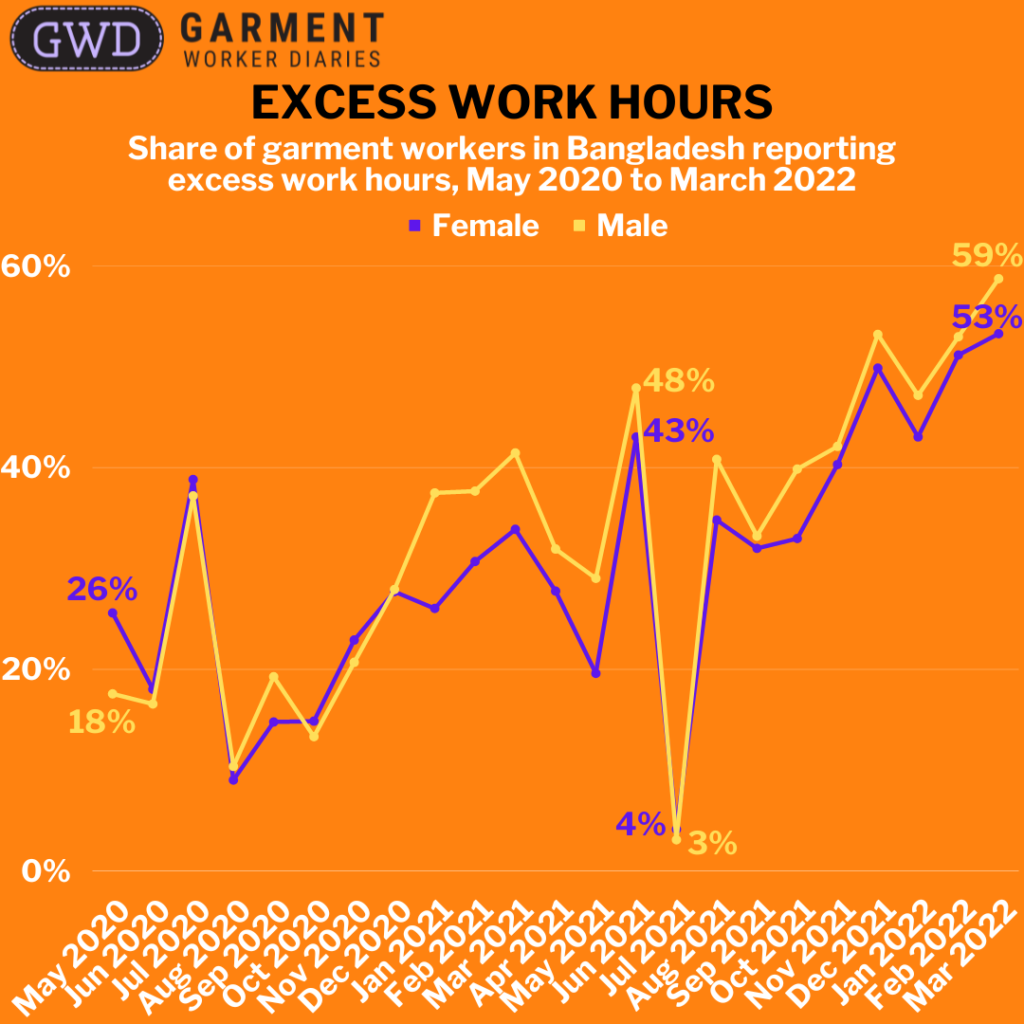

The government circular is an explicit acknowledgement of a phenomenon that the Garment Worker Diaries (GWD) has been documenting for many months now—that there has been a rise in the share of workers working excess work hours over the past year or more. For example, in our March monthly update we noted the large share of workers working excess hours. We followed this up in a recent webinar hosted jointly by MFO and SANEM in which we showed the steady climb in the share of workers working excess hours since August 2020. The Financial Express, The Business Standard, Fibre2Fashion articles on the government circular cite GWD data from the webinar.

The data show that in August 2020, a few months after the pandemic hit Bangladesh’s RMG sector and induced the government to lockdown the factories for a few weeks, about 10% of workers reported working excess work hours. The share of workers reporting excess hours increased to 35% for women and 41% for men by August 2021, and, for the first time since the pandemic, more than 50% of workers (50% of women and 53% of men) reported working excess hours in December 2021. The share dipped very slightly below 50% in January 2022, but remained above 50% for February and March—we will have April data soon.

What these data tell us is that more than half the workers in the RMG sector worked excess hours many months before the government circular permitted such a practice. The government’s solution to make this practice legal might work in the short-term—factory owners can continue to meet the demand from international brands, workers can cover their increasing living costs with the extra pay from the additional hours, and the country can earn much-needed foreign exchange to pay for the rising cost of oil and other imports.

But this solution is unlikely to be sustainable. Many workers are truly compelled to work excess hours because their normal wage is so far below what we have calculated to be a decent living wage (see Part 2 of our “Living Wage, Living Planet” series). But it is unclear how long they can sustain 12-hour days, 6 days a week, performing repetitive, physical tasks. This is especially the case as the GWD data suggest that excess hours do not yield a wage premium (see the February monthly update for more on this), even though the law requires that they be paid a premium for overtime. Factories may also not be able to rely on the excess work hours of their employees to sustain their production in the face of the European Union’s new human rights due diligence regulations and its commitment to Decent Work Worldwide. The EU initiatives will make it difficult for international brands selling in Europe to accept products made by workers working excess hours. These are near-term threats to the sustainability of the current business model. In the next 10 years or so, Bangladesh will become increasingly vulnerable to flooding due to the consequences of climate change. Bangladesh’s RMG sector factories are highly vulnerable to climate change due to their location in low-lying, flood prone areas (see Part 1 of the Living Wage, Living Planet blog series). They risk hastening their own demise with their high throughput production practices, which contribute to climate change.

The excess hours data coming out of the GWD initiative in Bangladesh, and the Government of Bangladesh’s own acknowledgement of the excess work hours phenomenon, require a long-term, sustainable response. It is not the role of this initiative to make policy recommendations, but merely to let the world know what the workers in the RMG sector in Bangladesh are experiencing and what they are telling us. In our next blog, we will dig deeper into the data and look at the extent to which workers are working excess hours in factories that supply major brands in the U.S. and Europe.