One of the issues the Garment Worker Diaries initiative in Bangladesh has been tracking is the ability of workers to be economically resilient in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Workers have had a tough 12 months, with the shutdown of the factories in late March and uncertainties over whether they would have jobs and get paid looming over them for many months after. Even today, as we see the workers earning salaries similar to the ones they were earning before the pandemic hit, there is still a worry that their jobs are not secure.

This week’s blog is the first in a series on how resilient workers were in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic and how resilient they might be in the future. In this blog, we discuss resilience itself—we define it, explain how we measured it using our weekly GWD survey, and describe what we found out about worker resilience. In next week’s blog, and subsequent blogs after that we explain what we found out about what made workers more or less resilient during the last 12 months.

Defining and Measuring Resilience

An individual or family that is economically resilient in the face of an emergency is one that can first avoid economic stress, through things like insurance (either private or provided by the government), but that can also withstand or cope with economic stress when it comes, and bounce back from it when circumstances improve. So resiliency is not just one characteristic, but a number of different characteristics that come into play at different stages of an emergency. Furthermore, resilience is not just an attribute of a family or individual, but also an attribute of the society they live in: is there government support available for families that suffer unemployment? Are people protected from extreme weather events by good infrastructure. This is why a well-off family that has good insurance is resilient even though, if it ever suffered economic stress, it might fall apart through a series of bad decisions. On the other hand, a low-income family with few protections is very vulnerable to something going wrong, and so less resilient, even though when things do go wrong that family responds in very appropriate ways that maximize the possibility that it will be able to bounce bank. Garment workers, as we shall see, definitely fall into the second category.

To track resilience the GWD initiative used a simple question that we asked the workers every week:

“During the past week, have you eaten less than you felt you should because there wasn’t enough money for food?”

|

Note: MFO and SANEM borrowed this question from a survey (see FSD061) that the U.S. Centers for Disease Control (CDC) developed many years ago as part of a series of questions on food security within a household. The only thing we changed was that we asked about the “past week” while in the CDC survey they asked about the past 12 months. |

We chose this question as a way to measure resilience because going without food is a sure sign that someone is living under economic stress and that they are being tested by the economic circumstances they are facing. Going without food might be a way to cope with an emergency situation, but it is not a sustainable coping mechanism because you lose strength, are less able to work, and become more vulnerable to disease. So going without food suggests that a person has not been able to avoid the consequences of an economic emergency, and it also suggests that they may have difficulty withstanding the impact of the emergency and bouncing back from it.

Garment Worker Resilience

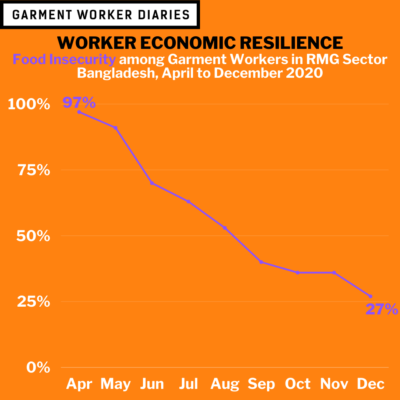

When we first asked workers in the RMG sector this question in April almost every single worker answered “yes” to it in at least one of the weeks when we interviewed them that month. This told us something important: garment workers were not in any position to protect themselves against an economic emergency. In May workers got support through the government support program for the RMG sector, and by June production had come back online and a vast majority of workers were back at work. Nevertheless, food insecurity persisted—it was only in September that less than half the workers answered “yes” to the question in at least one of the weeks we asked it that month. Food insecurity still persists today, with about one quarter of workers still answering “yes” to the question in one of the weeks each month. This means that even in normal times, in terms of earnings, workers are food insecure. Furthermore, there is no reason to believe that workers’ earnings are sufficient to enable them to buy themselves the protection they need through, for example, savings to avoid the economic impact of another emergency. And though the government did provide support to the RMG in 2020, the workers do not believe the government will help them in the future. But there may be some glimmer of hope regarding worker resiliency. We will look at where this hope might be coming from next week.

The data for the analysis presented here came from a subset of 732 workers in April 2020 and a subset of 1,269 workers from May 2020 onwards. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.