This week’s Garment Worker Diaries blog has been guest-written by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM), our partner in the field in Bangladesh. MFO and SANEM have been working together for over three years and SANEM was instrumental in helping to scale the GWD project to its current full capacity in Bangladesh. MFO is pleased to present this blog about how the 2018 Wage Gazette in Bangladesh might have had an impact on garment workers, which draws data from questions SANEM recently posed to respondents during the weekly interviews. We are also publishing the full blog in Bangla which you can find directly adjacent to this blog post on our Worker Diaries homepage.

***

The export-oriented ready-made garment (RMG) sector in Bangladesh has experienced stellar growth in the last three decades and made a significant contribution to the country’s development. In FY 2020-2021, as much as 83% of the total national export volume and 11% of Bangladesh’s GDP can be attributed to the RMG sector. But a significant number of garment workers themselves lead a substandard life with incomes placing them below the poverty line. To affect positive change in the workers’ lives and ensure minimum standards of living, in August 2018 the Bangladeshi government set the monthly minimum wage for entry-level positions to BDT 8,000 (i.e., grade VII) by dint of a gazette (within a governmental context, a gazette is periodical publication authorized by the government to make legally binding pronouncements). In nominal terms, this amount was 51% higher than the previous minimum wage of BDT 5,300 which had been in place since 2013. Prior to the finalization of the 2018 gazette, garment workers’ unions were demanding BDT 12,020 while garment factory owners offered BDT 6,360 during the negotiations among workers, owners and the government. In the end, the factory owners were unhappy with the gazette as it raised operational costs. However, the gazette was officially announced in December 2018. It is plausible to assume that stakeholders higher up the ladder from garment workers, such as factory owners and brands, have been taking measures to accommodate the additional cost burden of a higher minimum wage. And if these measures exist (for example, layoffs, higher production quotas), they might be impacting on workers.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh; numbers in graphs may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

To gauge what impact, if any, the 2018 gazette has had on garment workers, SANEM, in collaboration with Microfinance Opportunities (MFO), surveyed 1,278 of them in early November 2021. We restricted our full survey and subsequent analysis to just the sub-sample of workers who told us they were still working at the same factory since December 2018, which came out to 55% of the interviewed workers (36% of them had changed factories since the 2018 gazette, and the remaining 9% told us they were not working before the 2018 gazette).

We posed a series of questions to the workers who were still working in the same factory to determine if there had been any change in their work activities since the 2018 gazette. 58% of that sub-sample said that the most frequent work they currently perform is sewing, weaving, knitting and embroidery. Other current work includes activities such as fabric inspection, marking or cutting, dyeing, printing, and garment quality control. When we asked these respondents to compare their current work activities to their activities before the 2018 gazette, 51% of the workers told us they used to perform sewing, weaving, knitting and embroidery, a bit of a lower share than currently perform those activities. A relatively larger change occurred among workers who perform “sewing line help” activities: 11% of workers used to perform this type of work before the gazette announcement, and currently only 4% of workers perform these activities.

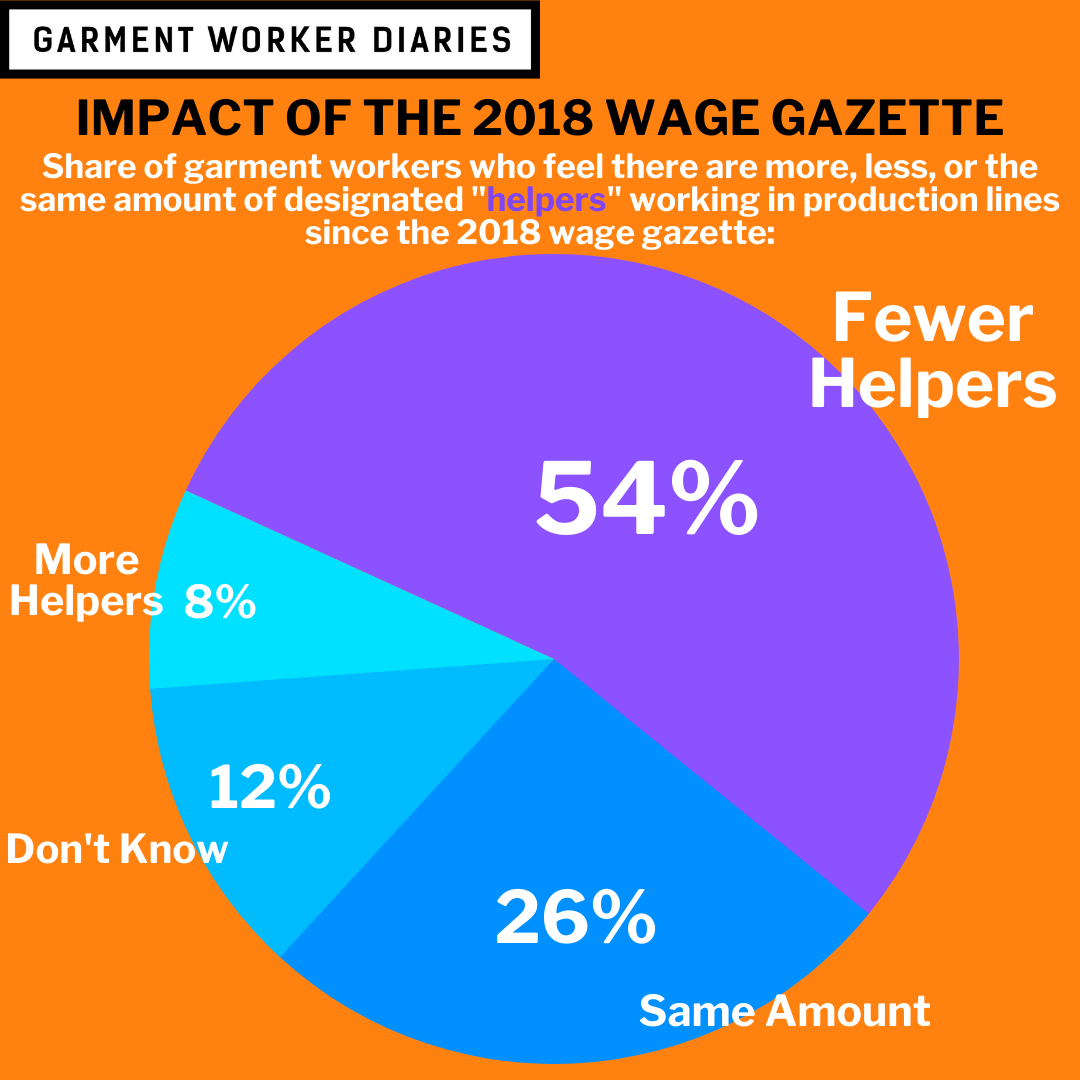

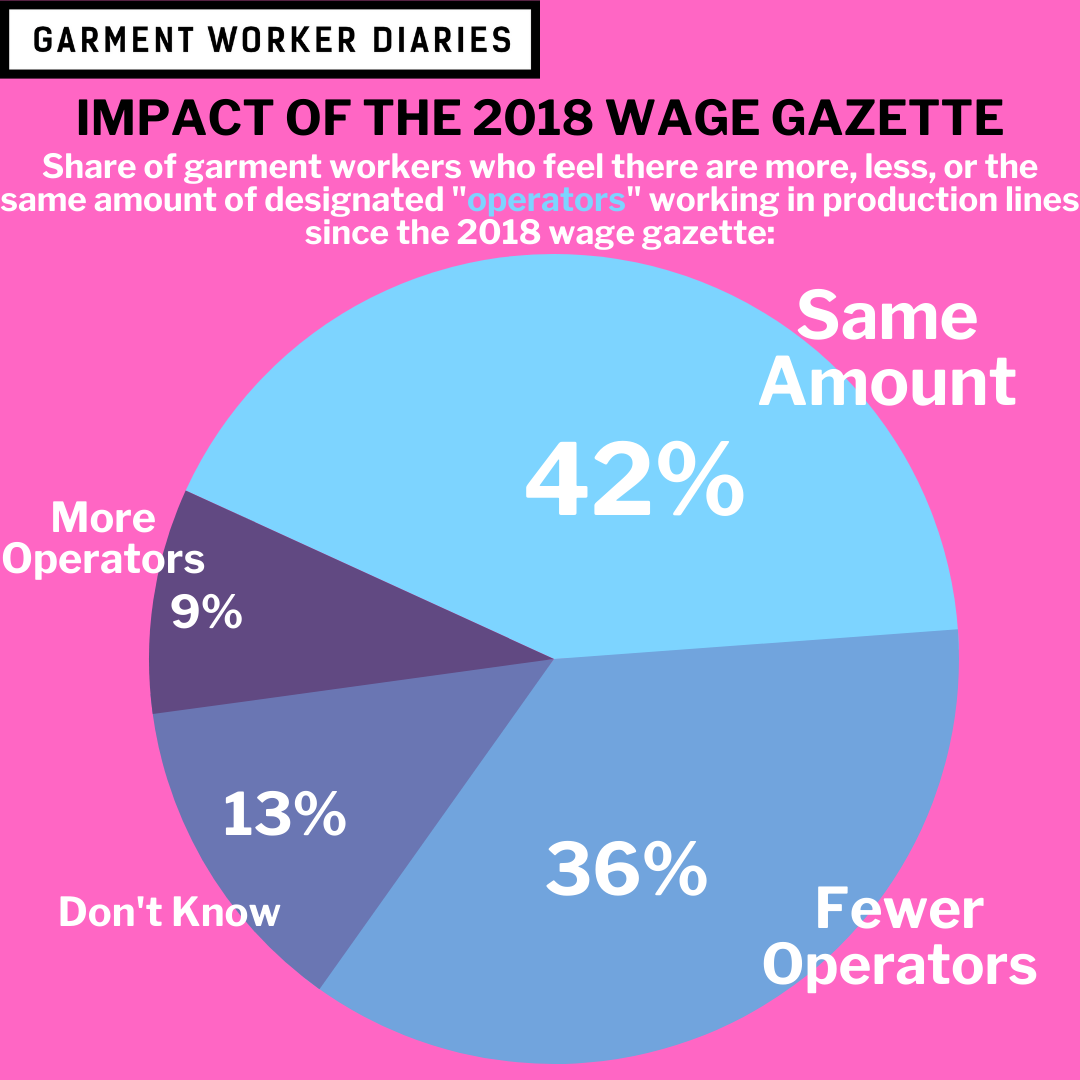

Currently, most of the workers surveyed told us that their job designation (distinct from the activities they perform) is “operator” (representing 67% of the sub-sample of workers still employed at the same factory); 16% of these workers have some other type of designation, 15% are designated as “helpers”; 2% are “supervisors”; and 1% did not know their designation. The share of workers designated as operators has grown since December 2018: 55% then to 67% now, which is somewhat of a large jump. And there has been an even larger change in the share of workers employed as helpers, as the proportion of workers designated as helpers declined to half of its original percentage (from 31% then to 15% now).

Among these workers who are still employed in the same factory, 79% are still working in the production line. Almost 63% of these production line workers said that their work scenarios changed since December 2018. For example, about half of the respondents said that before gazette, 11 to 20 workers used to work in one production line, but now 1 to 10 workers are employed in that line. To note, this could be an indication that some of the workers might have lost their job due to the gazette announcement.

Similarly, in the case of operators, 45% of production line workers said that the numbers of operators in a line have changed compared to the work environment before the gazette was imposed. On the other hand, 42% of the workers replied that they have similar work activity as before. Before December 2018, 43% of the workers said that more than 50 operators worked in one production line but now the number has drastically declined as only 29% of the workers noted that more than 50 operators work on the production line.

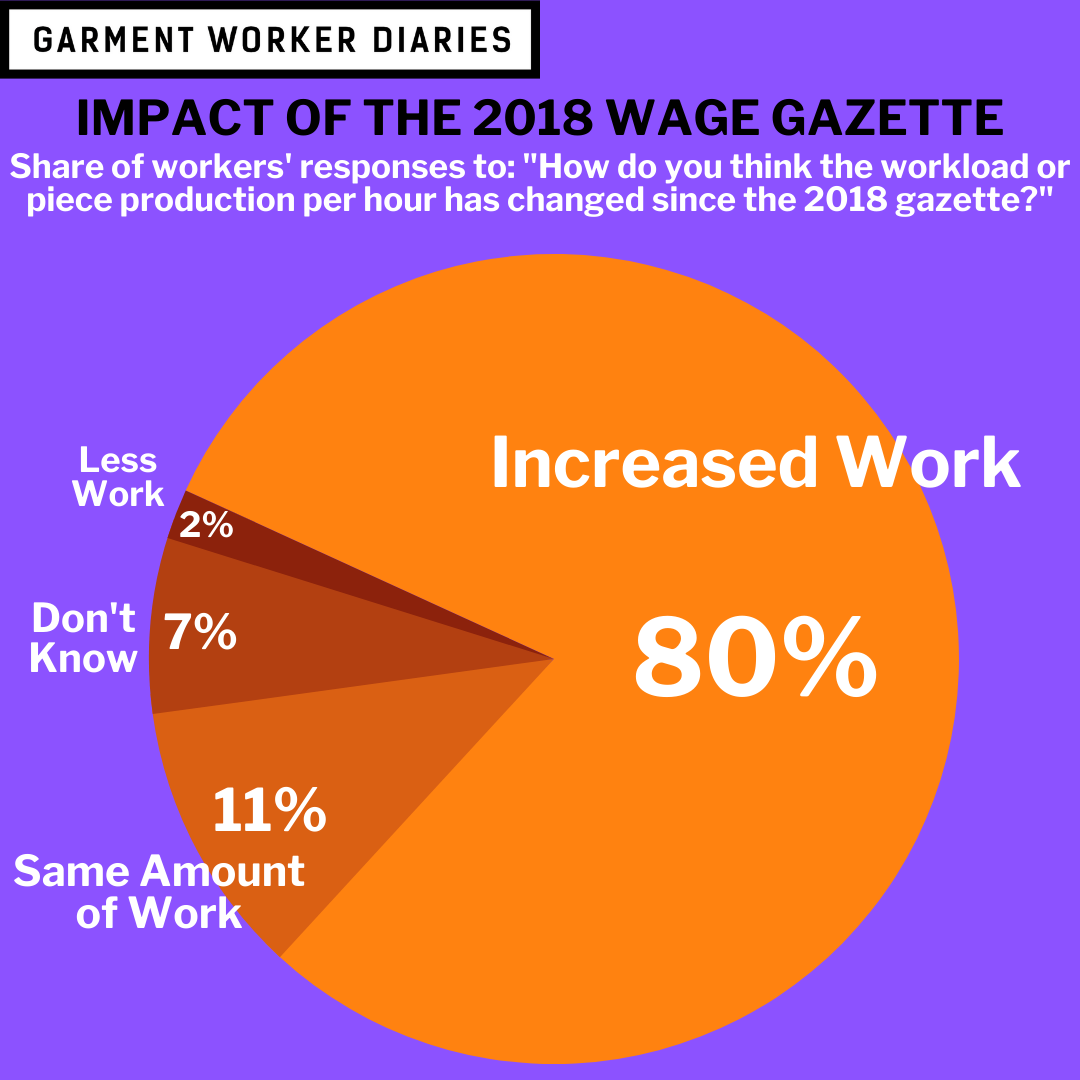

In terms of each individual worker’s workload, 80% of those respondents still working at the same factory told us that the production pressure has increased compared to before the 2018 gazette. Moreover, 58% of the production line workers stated that they do not get enough break after they finish work in their respective lines. In addition, more than half of these workers reported that they must move to another line after completing their own line’s duties.

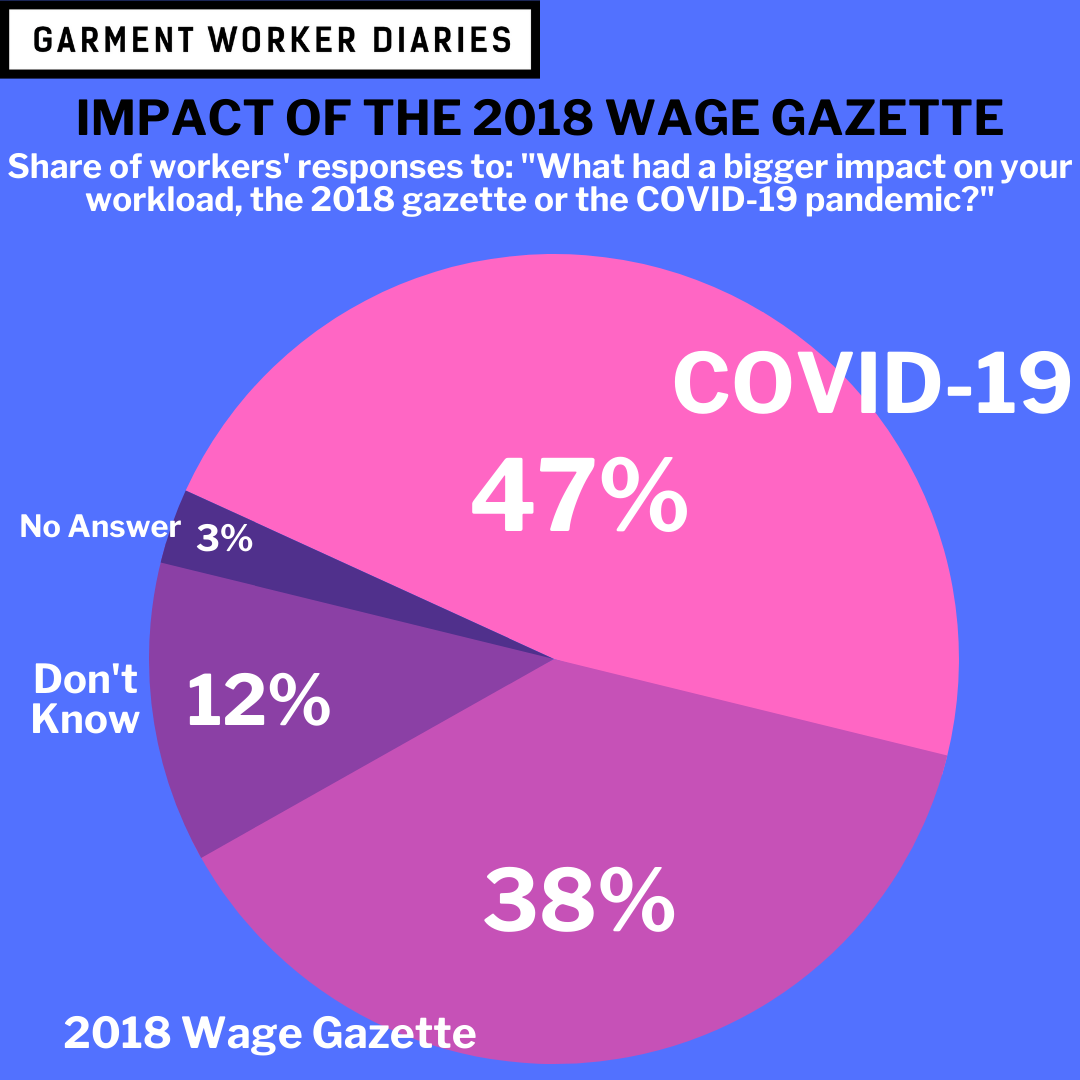

Lastly, it should be mentioned that the changes in work scenarios and workload may have been jointly induced by both the 2018 gazette and the COVID-19 pandemic. We asked all workers (including those who had changed factories since 2018 and those employed post-2018) which impacted their workload more: the 2018 gazette announcement, or the COVID-19 pandemic. Surprisingly, 47% stated that the COVID-19 pandemic had a greater impact on their work. A significant share of workers, 38%, did state that the 2018 gazette was the more impactful development (the remaining workers weren’t sure or did not answer). Thus, while both the 2018 gazette announcement and the COVID-19 pandemic have impacted daily factory life in the minds of garment workers, more research is needed to determine the specific magnitude of each historic development.

Among the 1,278 surveyed respondents, 76% (972) workers were female and 24% (306) workers were male. The workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). The share of respondents who are women is roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.