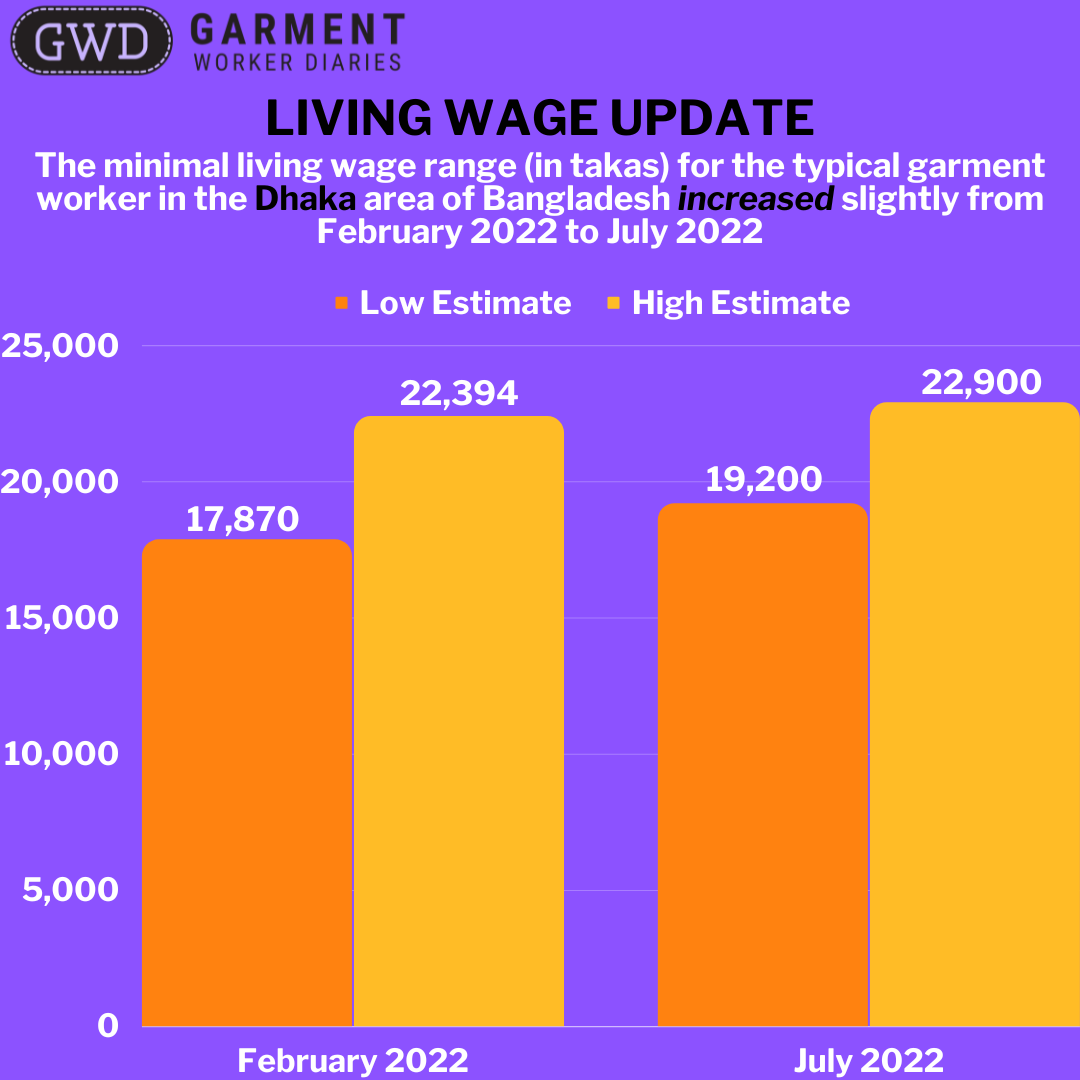

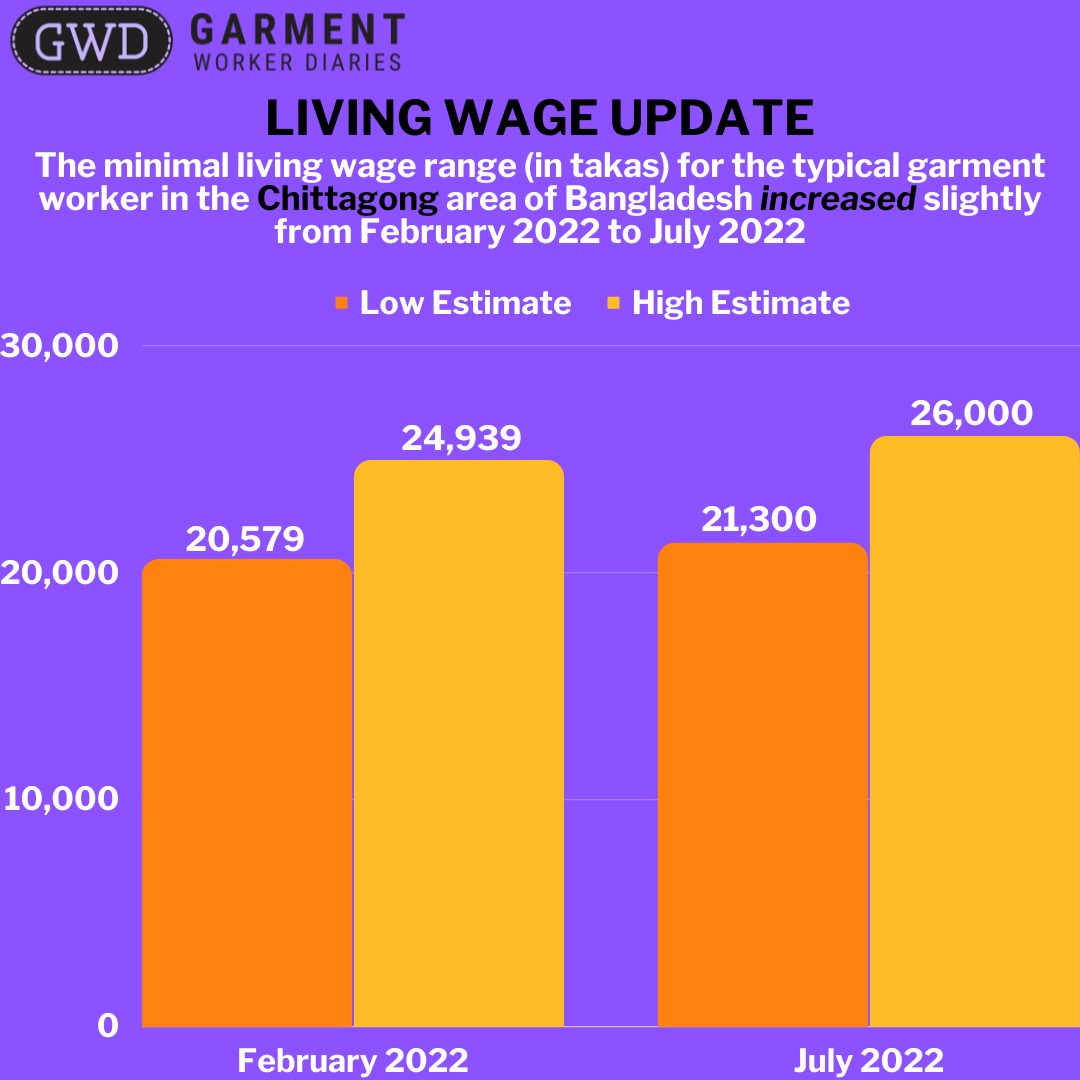

In May of last year we shared with you our first living wage calculations for garment workers in Bangladesh. Those calculations were based on data collected from garment workers in February. Then this past September, in part three of our “Living Wage, Living Planet” blog series, we shared with you an updated living wage calculation based on new data obtained from garment workers in July. What those new calculations show is that in two key garment producing areas of Bangladesh, Dhaka and Chittagong, the minimal living wage range had increased since early 2022.

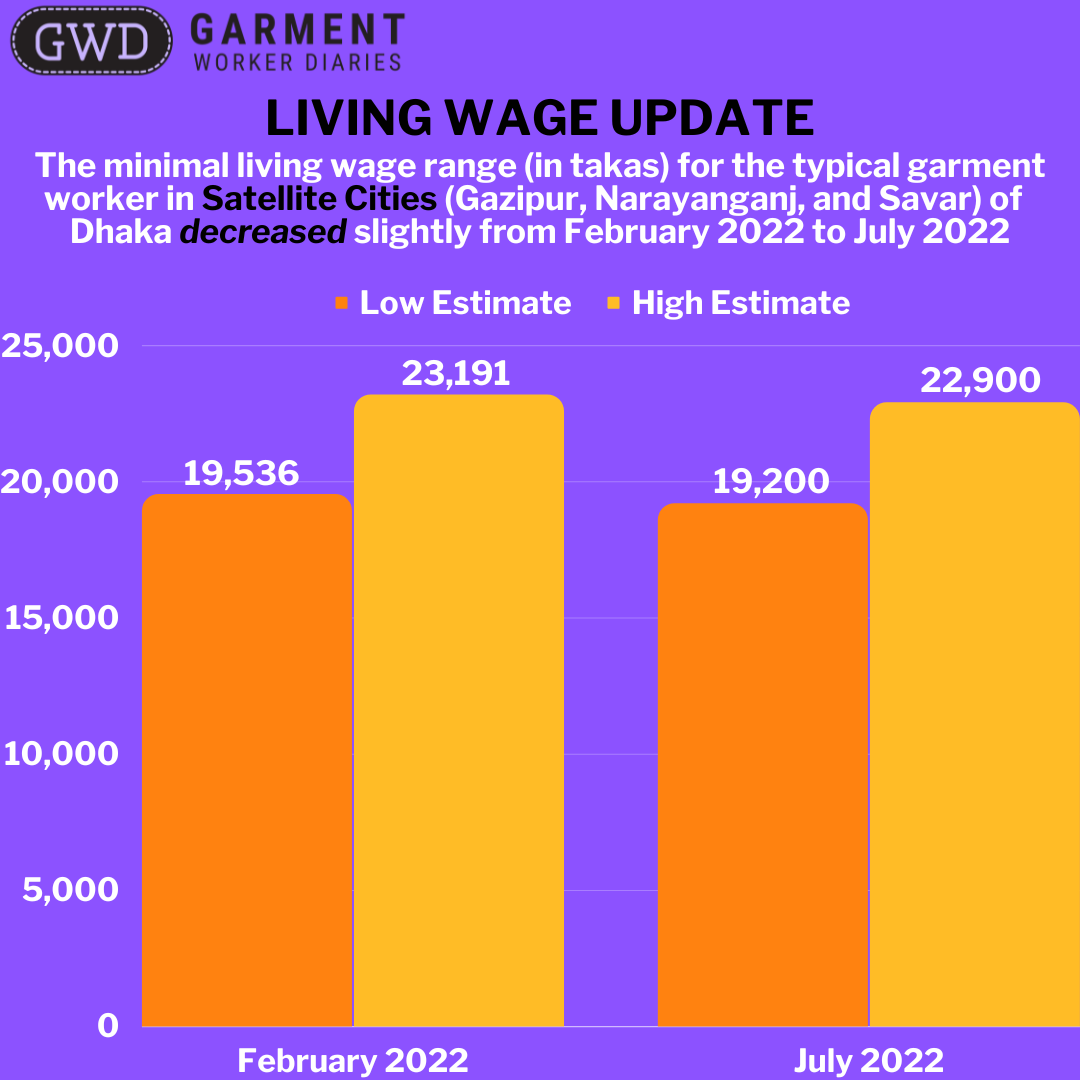

Below is a chart showing our minimal living wage ranges for February 2022, July 2022, and the change in range calculations over that six-month period. To remind you, the “low” end of our range estimates housing costs for a 3-room house (one bedroom for kids, one for adults, and a shared family room), and the “high” end of our range incorporates two additional rooms which are not typical: a private bathroom and a private kitchen (instead of the shared versions of those rooms, which are more typical for garment workers’ households and commonly accessed by about seven separate families).

| February 2022 (in takas) | July 2022 (in takas) | % Increase/Decrease (+/-) | |||||||

| Satellite Cities* | Dhaka | Chittagong | Satellite Cities | Dhaka | Chittagong | Satellite Cities | Dhaka | Chittagong | |

| Low | 19,536 | 17,870 | 20,579 | 19,200 | 19,200 | 21,300 | -2% | 7% | 4% |

| High | 23,191 | 22,394 | 24,939 | 22,900 | 22,900 | 26,000 | -1% | 2% | 4% |

*Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar

Again, just to remind you, we calculate the cost of a decent living wage by incorporating the following expenses:

- Housing costs

- Food costs

- Non-food, non-housing costs

- A small margin for unforeseen events

While part three of this blog series already provided an in-depth explanation of our methodology in estimating housing costs, this blog post, the fourth in the series, will provide further explanation of the other expense calculations included in our living wage proposals. We make the case that living wage calculations need to be reflective of changing realities on the ground. And the only way to do this is to remain in constant, direct conversation with the beneficiaries of living wage calculations, who in our case are represented by the garment workers of Bangladesh.

Methodology: Food Expenses

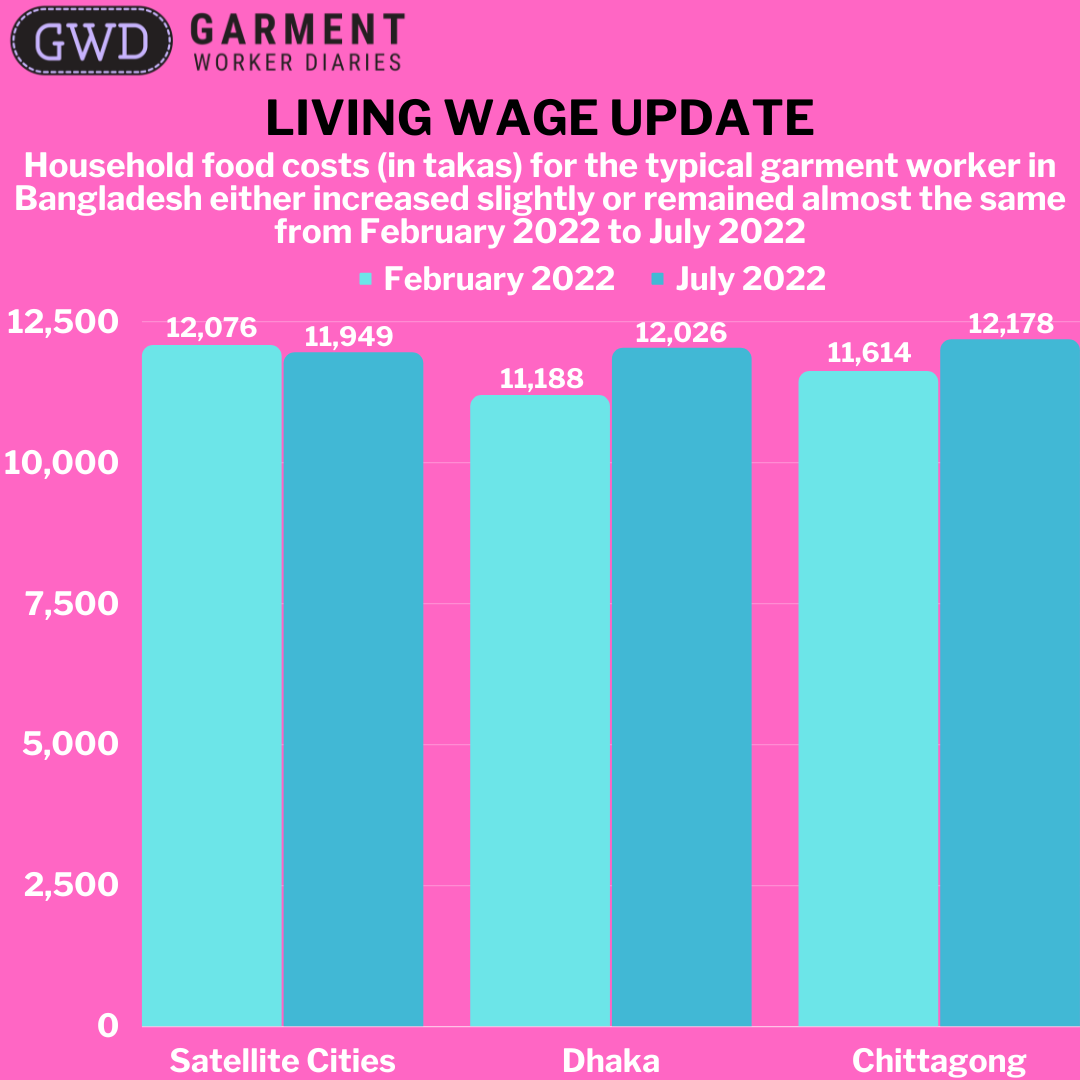

Some of the increase in our living wage calculation can be attributed to the rising price of food items. Below is a chart showing the increase in household food costs from February to July:

| February 2022 (in takas) | July 2022 (in takas) | % Increase/Decrease (+/-) | |||||||

| Satellite Cities | Dhaka | Chittagong | Satellite Cities | Dhaka | Chittagong | Satellite Cities | Dhaka | Chittagong | |

| Household Food Costs per Month | 12,076 | 11,188 | 11,614 | 11,949 | 12,026 | 12,178 | -1% | 7% | 5% |

What this means is that for the typical garment worker in Bangladesh, food costs were on the rise over the course of 2022, and in the best-case scenarios (in those satellite regions around Dhaka) the price of food decreased by just one percentage point.

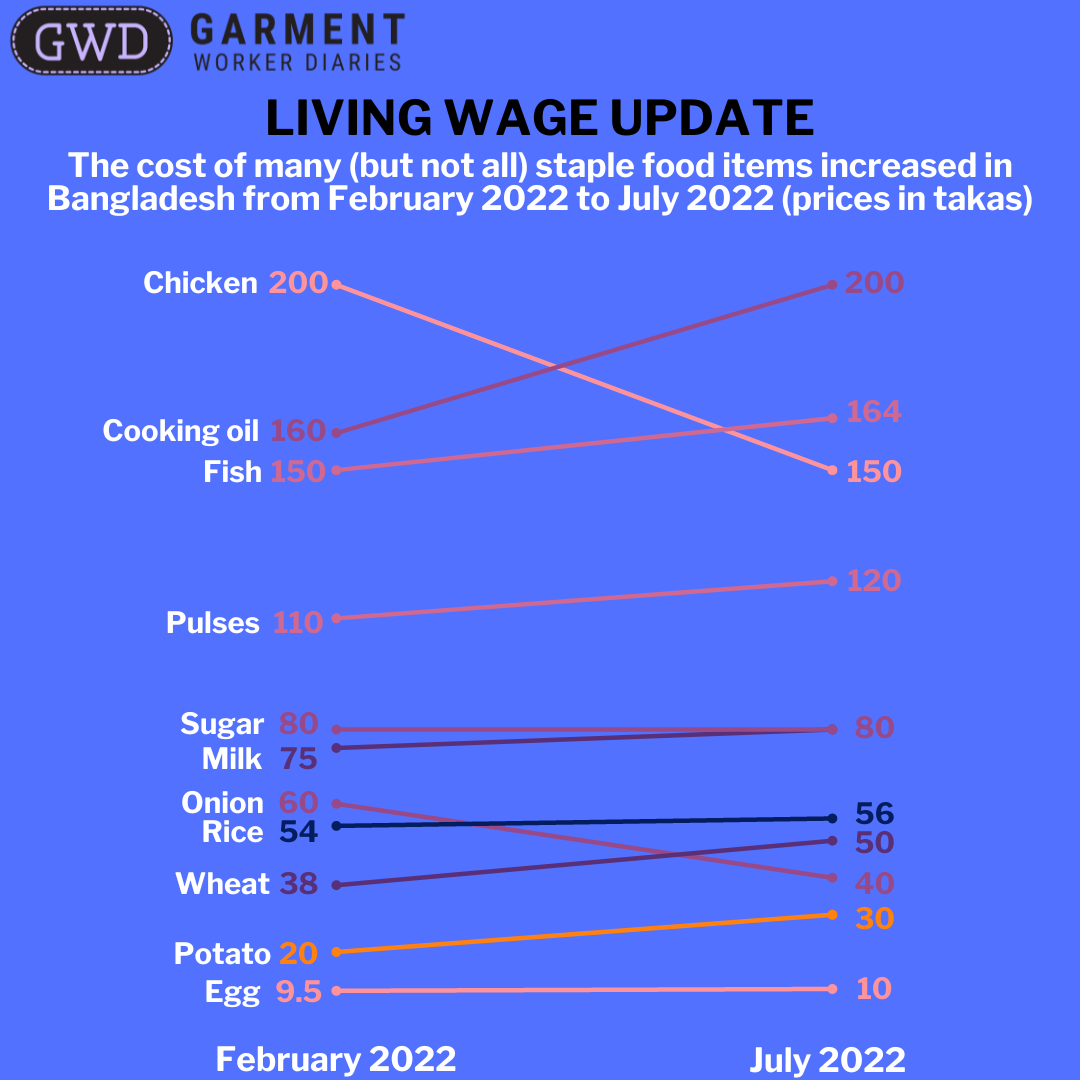

We feel confident in these numbers because we asked garment workers directly to describe for us their weekly consumption of certain staple food products, such as rice, pulses and vegetables. We also compared these numbers to consumer price indexes prepared by the Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Below is a chart showing the increase (or decrease) in a few of these staple food products from February to July:

| Model diet + food costs (taka) per person per day (Anker et al., 2016) | Feb 22 | Jul 22 |

| Food item | Cost per Kg (takas) | Cost per Kg (takas) |

| Potato | 20 | 30 |

| Onion | 60 | 40 |

| Wheat | 38 | 50 |

| Rice | 54 | 56 |

| Milk | 75 | 80 |

| Sugar | 80 | 80 |

| Pulses | 110 | 120 |

| Chicken | 200 | 150 |

| Fish | 150 | 164 |

| Cooking oil | 160 | 200 |

| Egg (cost per egg) | 9.5 | 10 |

As of the date of this blog’s publication, we have not yet had the opportunity to interview workers to get an update from them on how their grocery shopping is faring as 2023 begins. But if the consumer price index for January 2023 is any indication, the cost of food has still not returned to the amounts we were seeing at the beginning of 2022. Finally, we believe that food costs for satellite areas dropped slightly from February 2022 to July 2022 due to decreases in the price of chicken and fruit over that same time period. But we can’t be certain about that, and only further interviews will shed light on why food costs in the urban areas surrounding Dhaka did not increase at the same rate.

Methodology: Non-Food, Non-Housing (NFNH) Costs

NFNH needs of families include clothing and footwear; furniture and household equipment; health care; education; recreation and culture; phone bills; personal care, etc. Because of the difficulty and time needed to decide on appropriate standards for calculation of the many NFNH costs, the Anker methodology bases this calculation largely on secondary data. According to the 2010/11 HIES, 55.7% of the urban household expenditure for households at the 40th percentile of the urban household income distribution in Bangladesh is spent for food and beverages, 16.7% is spent for housing, and 27.6% is spent for all other expenditures. This means that the ratio of NFNH to Food expenditure at this point is 0.50. After some adjustments, a NFNF to food expenses ratio of 0.57 is used to estimate NFNH costs for the calculation of a living wage.

In our previous living wage calculations in February 2022, we used primary data obtained from respondents themselves for this estimation. However, due to the seasonality and complexity of these expenses, we have changed the methodology , and currently use a 0.57 NFNH costs to food cost ration for this estimate.

Marginal Expenses

In addition to housing, food, and non-housing non-food costs, we incorporate a small marginal expense for unforeseen events which include sustainability, emergencies and some assistance to parents.

As a conclusion, we feel it is important to remember that minimum wage boards in Bangladesh meet only so often, and it can be difficult to determine whether or not any proposed increases in minimum wages accurately reflect the purchasing power a garment worker’s wages affords them. However, by staying in constant communication with garment workers, as is made possible through the Garment Worker Diaries channels, policymakers can make more informed decisions affecting the lives of workers badly in need of a decent living wage.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh.