The European Union’s new human rights due diligence regulations and its commitment to Decent Work Worldwide have significant implications for global supply chain operations. In its effort to combat forced labor and child labor, in February 2022 the EU declared it will “grant unilateral trade preferences on the condition that benefitting countries comply with international labour standards, including on the elimination of child and forced labour.” The announcement broaches a broader conversation about what constitutes forced labor, and can therefore bar a supplier, such as a garment exporter, from participating in trade.

Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh

The International Labour Organization (ILO) defines forced labor as: “all work or service which is exacted from any person under the menace of any penalty and for which the said person has not offered himself voluntarily”. The ILO identified the elimination of all forms of forced or compulsory labor as a fundamental labor right, which is covered by the fundamental ILO Conventions No. 29 and 105. For a country like Bangladesh, where the RMG sector accounts for 80% of its export earnings, the examination of forced labor is particularly important.

In the first blog in this series on excess work hours, we documented the increasing share of workers working excess hours in the first quarter of 2022. In addition, data from a living wage calculation we performed recently suggests that there is a large gap between what workers currently earn, about EUR 122 per month, and what would constitute a minimal living wage. Depending on the assumptions made and the gender of the worker, the current gap is between EUR 66 and EU 132 per month. Putting these two findings together, there is plenty of evidence that workers have a financial incentive to work excess hours—it is the only way they can hope to get close to earning a decent wage each month. But, beyond this financial incentive, do workers feel forced to work excess hours?

To answer this question, we asked the workers two simple questions in one of the weekly interviews we conducted in June 2022. The questions focused on overtime because workers make no distinction between legal overtime and excess work hours. The question is also in line with Bangladesh labor law, which prohibits involuntary, forced overtime:

- When you are asked to work overtime, are you given the choice to not work overtime?

- What happens if you are asked to work overtime but cannot stay to work overtime?

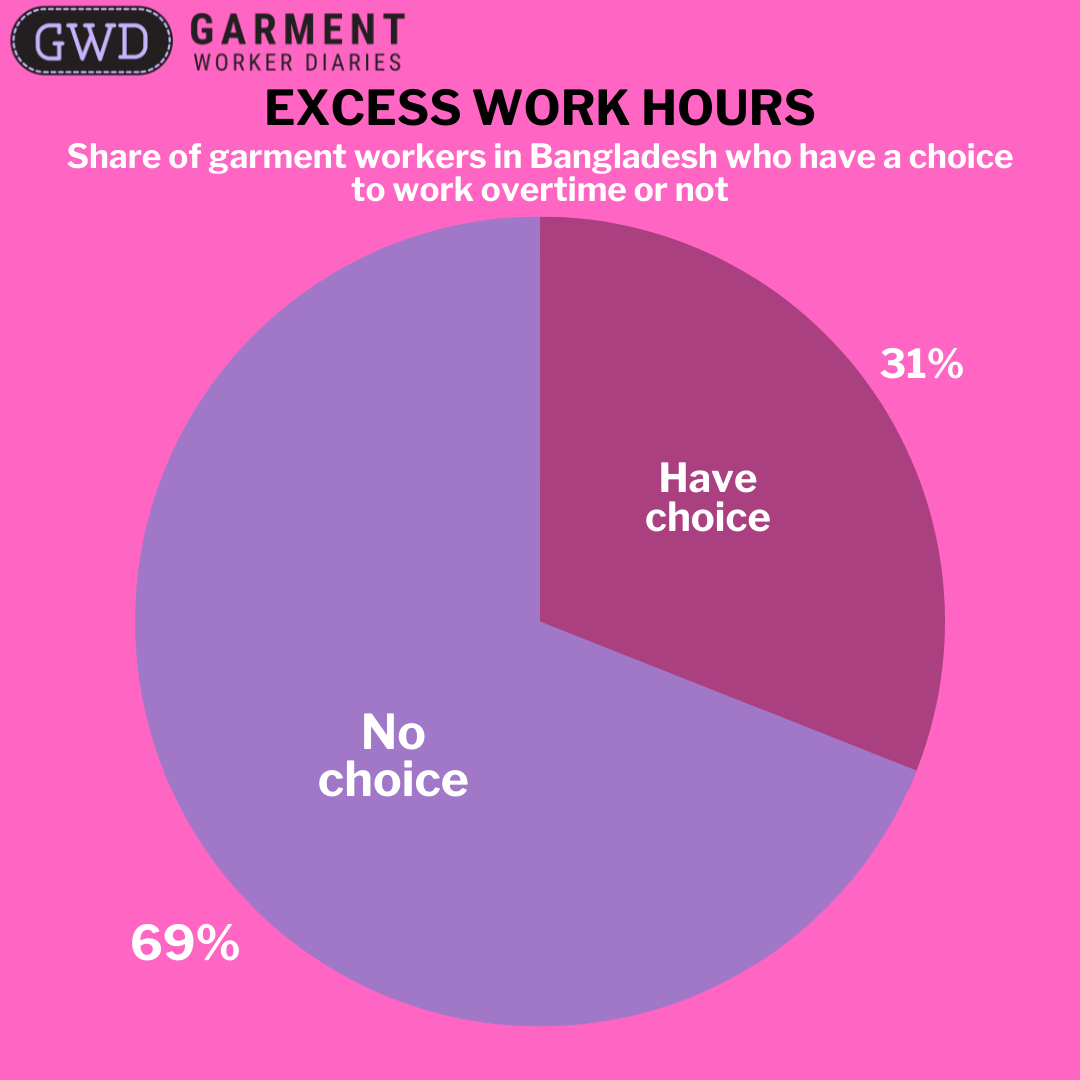

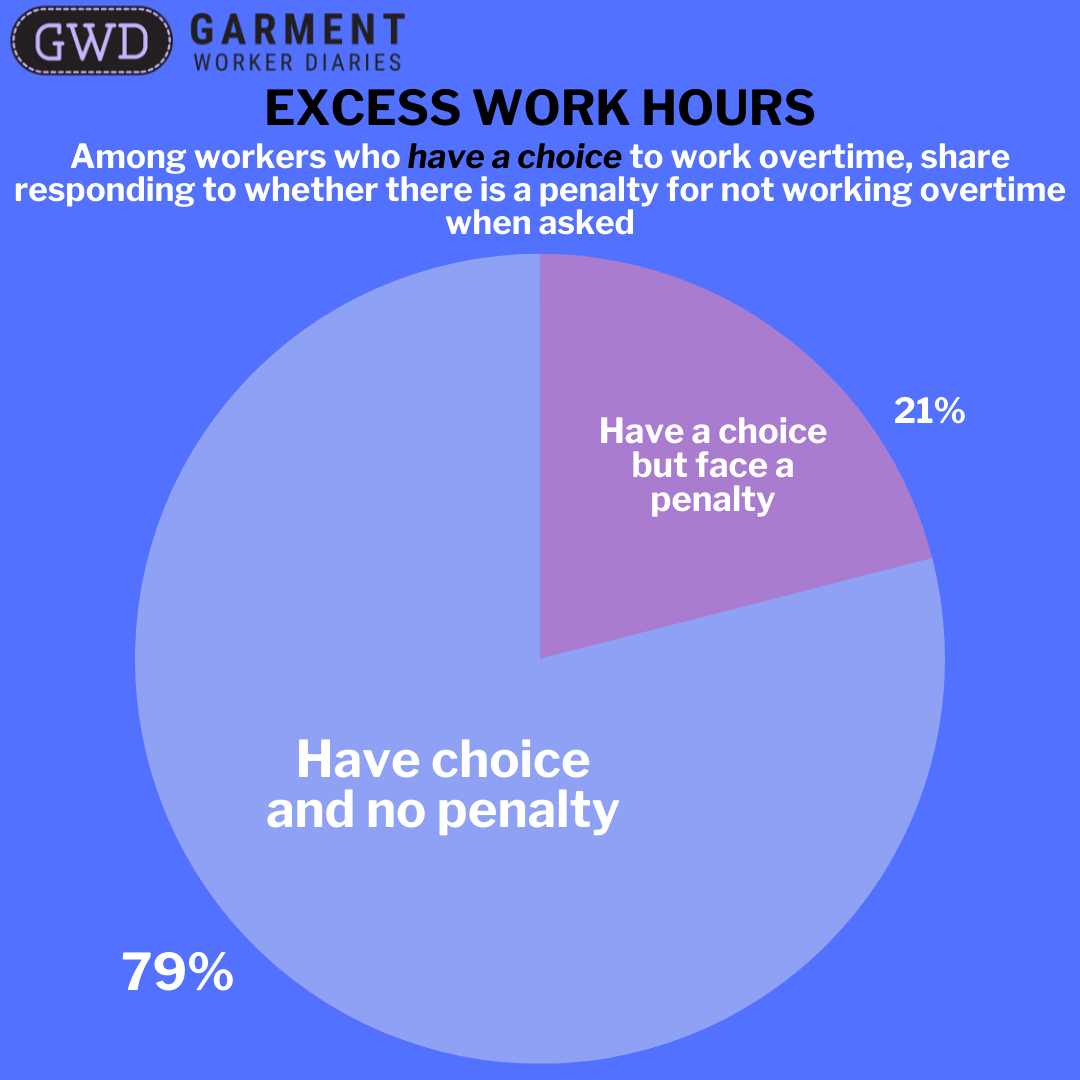

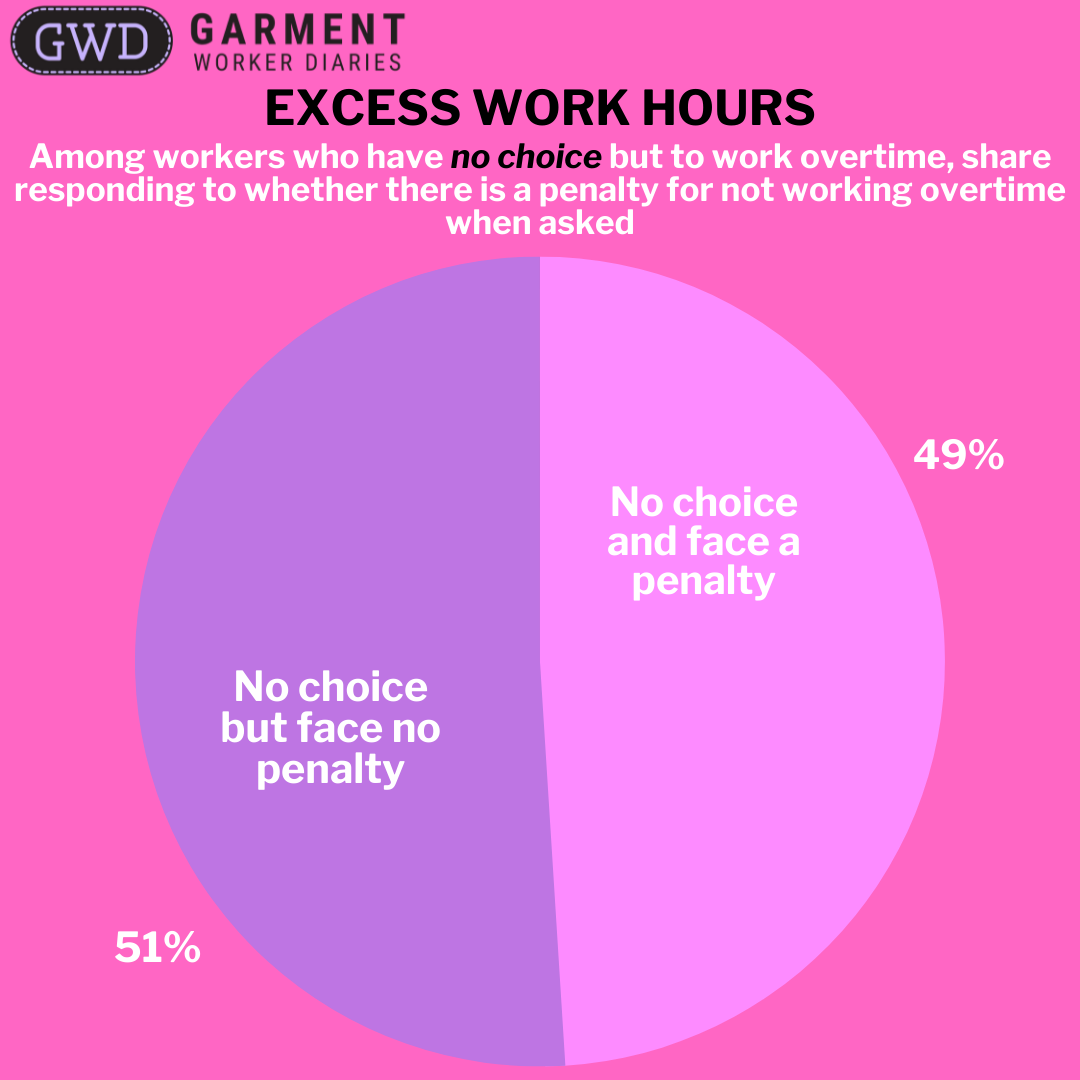

We posed the above questions about the choice to work overtime to 1,066 workers (784 women, 282 men) who were working during the week when we conducted this round of interviews—another 209 were not working that week. What we found was that just over two-thirds (69%) of workers said they did not have a choice as to whether to work overtime or not. Given the representativeness of the GWD sample, this translates to about 2.75 million workers without a choice about their work hours beyond the 8-hour workday. About half of those who said they had no choice said they faced some sort of penalty, most likely a verbal reprimand, if they refused to work overtime. About one quarter of those who said they did have a choice said they still faced a penalty for not choosing to work overtime, again most likely a verbal reprimand.

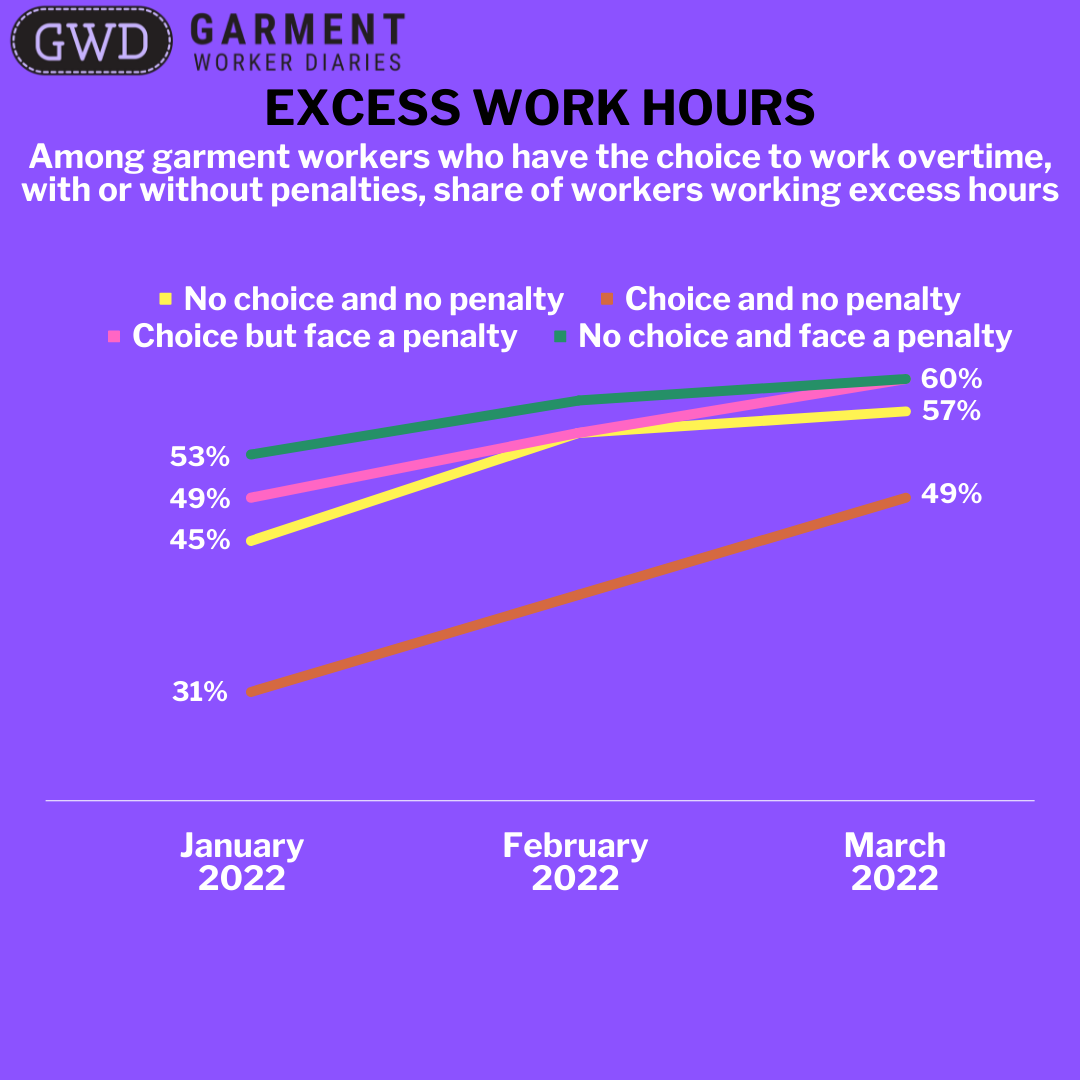

The workers’ perceptions of their ability to choose to work or not, and the potential penalties they face have consequences for the number of hours they work and the likelihood that they work excess hours. Focusing on data from January to March 2022, the months right before the government changed the rules about legal work hours (see our earlier blog in this series, Excess Work Hours Part One), we see that workers who stated that they had no choice about working overtime and faced some sort of penalty for not working were the most likely to work excess hours in those months—depending on the month, between 53% and 60% of them worked excess hours in the January to March period. Those who said they had a choice but faced a penalty if they chose not to work were the next most likely to have worked excess hours in the first quarter of 2022—between 49% and 60% depending on the month. Those who said they had no choice but faced no penalties for not working overtime were slightly less likely to have worked excess hours—between 45% and 57%. The least likely to have worked excess hours were those who said they had a choice about working overtime and faced no penalty if they did not—from 31% to 49% worked excess hours in the first quarter of 2022, although even here we see that by March 2022 almost half worked excess hours.

Put together, this evidence suggests that over two-thirds of workers feel they have no choice in working overtime or not, and that this lack of choice often, and increasingly, translates into work hours that exceed the legal limit allowed under Bangladesh law. The government’s recent change to the law may make more of the hours worked “legal”, but workers’ ability to choose whether to work those hours are unaffected. It is not clear how the EU, with its renewed focus on forced labor, will address the situation in Bangladesh. But the scale at which it is occurring—affecting about 2.75 million workers—warrants the attention of policy-makers.

The data are drawn from interviews with about 1,300 workers interviewed weekly from January 2022 to June 2022. The number of worker responses in a particular month varies depending on interview participation rates throughout the month but were never below 1,210 during this period. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.