In last week’s blog MFO and SANEM updated the Garment Worker Diaries project through January 2021. We also revealed that the work hours and wages for garment workers in January were the highest we’d seen yet during the COVID-19 pandemic. What this indicates for us is that the majority of garment workers in Bangladesh are working and earning as much as they would have before the pandemic, despite reports of a global downturn in apparel purchases (by both brands and consumers alike) and a cash crunch among factory owners.

However, we understand that “business as usual” is not the case for all workers in our study. We wanted to get a sense of whether or not the type of factory a respondent works for has a statistical correlation with their work hours, wages, health, food security and other work-and-life metrics. To do that, we analyzed the January 2021 data we have for the brand-facing and non-brand facing factories in our sample (brand-facing being defined as those factories who are verified suppliers to specific brands appearing on publicly available supplier lists or in the Mapped in Bangladesh data set). Because we know that brands tend to try to publicly list their Tier 1 suppliers (as these types of factories are cutting, knitting and sewing together a brand’s tee shirts, jeans, and other items of clothing) before identifying and listing their Tier 2 and Tier 3 suppliers (which are further removed down the supply chain). We might assume that if a factory in our sample is brand-facing, there is a greater chance that it is a larger, wealthier Tier 1 factory than a smaller, less wealthy Tier 2 or 3 factory.

But we cannot know this for sure, so for the current analysis we will stick to calling the two types of factories in our sample “brand-facing” and “non-brand facing”. Even so, some interesting, statistically significant differences can be detected between these two types of factories in Bangladesh. Let’s see what that means for the respondents who work there.

One further thing to note before reading on. In what follows we identify whether the differences in the results for workers in brand-facing and non-brand-facing factories are “statistically significantly” or not. What we are doing here is using the language of statistics to tell you whether a difference between two numbers, say the monthly pay of a worker, is a real difference or not. Statistics are never completely accurate and, therefore, the differences between two statistics are never fully accurate. But a statistically significant difference is one that is big enough that it is not the result of these inaccuracies.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Dhaka. Numbers in graphs may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Employment

There was no statistically significant difference in the amount of hours worked in January 2021 when comparing respondent who worked at brand-facing factories and those who didn’t (brand-facing factories’ employees worked a median of 263 hours compared to 259 median hours for non-brand facing employees).

Two statistically significant differences we did find, however, concern factory closures and suspensions. Of the 15% of non-brand facing respondents who didn’t work in January, 14% of those workers were unemployed due to factory closures. In contrast, of the 12% of brand-facing respondents who did not work in January, only 4% of those workers were unemployed due to factory closures.

These data suggest that brand-facing factories are faring better. But the data are more nuanced than this. Take, for instance, suspensions: a greater proportion of the unemployed workers at brand-facing factories, 11%, were “suspended” from work than those unemployed workers at non-brand facing factories, where only 3% were suspended in January (“suspended” means that a worker is still employed at a factory, but not working and not getting paid because there is not enough work to go around).

Salary Payments

88% of respondents employed at brand-facing factories received a salary in January, a statistically significant difference (based on our sample size) compared to the 83% of respondents employed at non-brand facing factories who got paid in January. The difference in the amount of salary workers at each type of factory received was also statistically significant: the median salary for brand-facing workers was Tk. 11,200 compared to Tk. 10,000 for non-brand facing workers. Data from December suggest that workers in both types of factory worked roughly the same number of hours, and, as a result, brand-facing workers were paid, on average, 5 taka per hour more than non-brand-facing workers (48 taka vs. 43 taka per hour)—a statistically significant difference.

Digital Payments and Financial Transactions

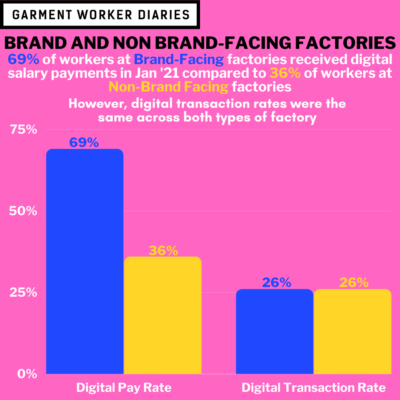

Looking at whether or not a respondent received their salary digitally produced a large statistically significant difference: employees of brand-facing factories received their salary digitally at a rate of 69%, compared to 36% for employees of non-brand facing factories.

However, having their salary already existing as digital currency did not translate into more frequent digital financial transactions for brand-facing workers. There were some types of financial transactions in January where brand-facing workers were more likely than non-brand facing workers to use a digital method, such as for withdrawals and savings, but this is perhaps obvious due to brand-facing workers being paid digitally at a higher rate. In fact, for only one type of transaction, sending money transfers to people in one’s network outside the household, was there a somewhat wide difference between brand-facing and non-brand facing workers’ preferred method of transacting: 65% of the money transfers sent by non-brand facing workers to people in their social networks were digital, compared to 53% of money transfers sent by brand facing workers. But again, while this gap was noticeable, it was not statistically significant.

There were a few areas of statistically significant comparison between the financial transactions of brand-facing and non-brand facing employees. The frequency of financial transactions (no matter whether the method was digital or cash-based) was generally a bit higher across the board for employees of brand-facing companies. Specifically, this means that brand-facing employees were a bit more likely to make transfers to someone within their household, receive loans, repay loans, receive and send transfers from/to someone outside their household, and make withdrawals from and deposits to savings.

Brand-facing and non-brand facing employees differed the most in the frequency of loans received and repaid, and the amount of loans received was also significantly higher for brand-facing employees, suggesting that employees of brand-facing factories have a higher debt capacity than workers at non-brand facing factories.

The amount of savings brand-facing employees reported was also statistically higher than the savings reported by non-brand facing employees.

Food Security and Health

Health and wellness-wise, the only statistically significant difference we detected between brand-facing and non-brand facing employees was in the rate of household illness reported: 28% of brand-facing employees reported a household illness in January compared to 23% of non-brand facing employees.

Other factors, such as food security, rate of injury and the ability to seek medical help were statistically on par with one another when comparing employees from the two types of factories.

The monthly data for January 2021 presented here come from interviews conducted over the phone with a pool of 1,260 workers. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.