While much has been written about the introduction of automated manufacturing processes into apparel factories, there is not yet conclusive evidence or agreement that automation is a good or a bad thing: one’s vantage point seems to be a crucial element. One fact there does seem to be agreement on is that automation has the potential to impact stakeholders across the entire global supply chain.

The respondents in the Garment Worker Diaries study in Bangladesh are just such stakeholders. Automation is often regarded as a threat to these workers, who are in possession of just the types of low-wage jobs common in the apparel industry. So, what are garment workers’ attitudes towards automation then? We believe it is necessary to ask workers about their experiences with automation, and that by adding their voices to the conversation we are broadening the communication channel that connects brand executives, factory owners, workers and consumers.

We recently conducted a survey in which garment workers were allowed to share with us their own experiences with automation (within the context of the introduction of new machines to their assembly lines) and their feelings about these experiences. What follows are the results of these interviews.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh; numbers in graphs may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Methodology

MFO spent a few weeks in February and March 2022 researching what has recently been written about automation in the apparel industry. We also researched questionnaires that had been presented to other workers in other types of manufacturing industries and who are encountering automated or computerized processes in their own trades.

Our next step was to understand the language garment workers use when they think about automation. We did this by asking our 130 of our worker leaders a simple question: “What, if any, changes in how you complete your work tasks have you experienced in the last two years?” Many worker leaders referenced the introduction of new machines to their line. As one worker leader said: “I am currently the senior operator. Earlier, I used to work on the Bangla machine to sew. Now I sew using the automatic machine.”

Using the motif of new machines, we devised our own automation questionnaire and on April 1st presented it to the full study sample of garment workers in our study as part of the regular weekly survey.

Results

The first question we asked respondents was:

Have you ever had to change how you complete your work tasks because you were required to work on a new machine?

If workers did not respond “yes” to this first question we asked them the following:

Have you ever seen a change in how other people in your workplace complete their work tasks because they were required to work on a new machine?

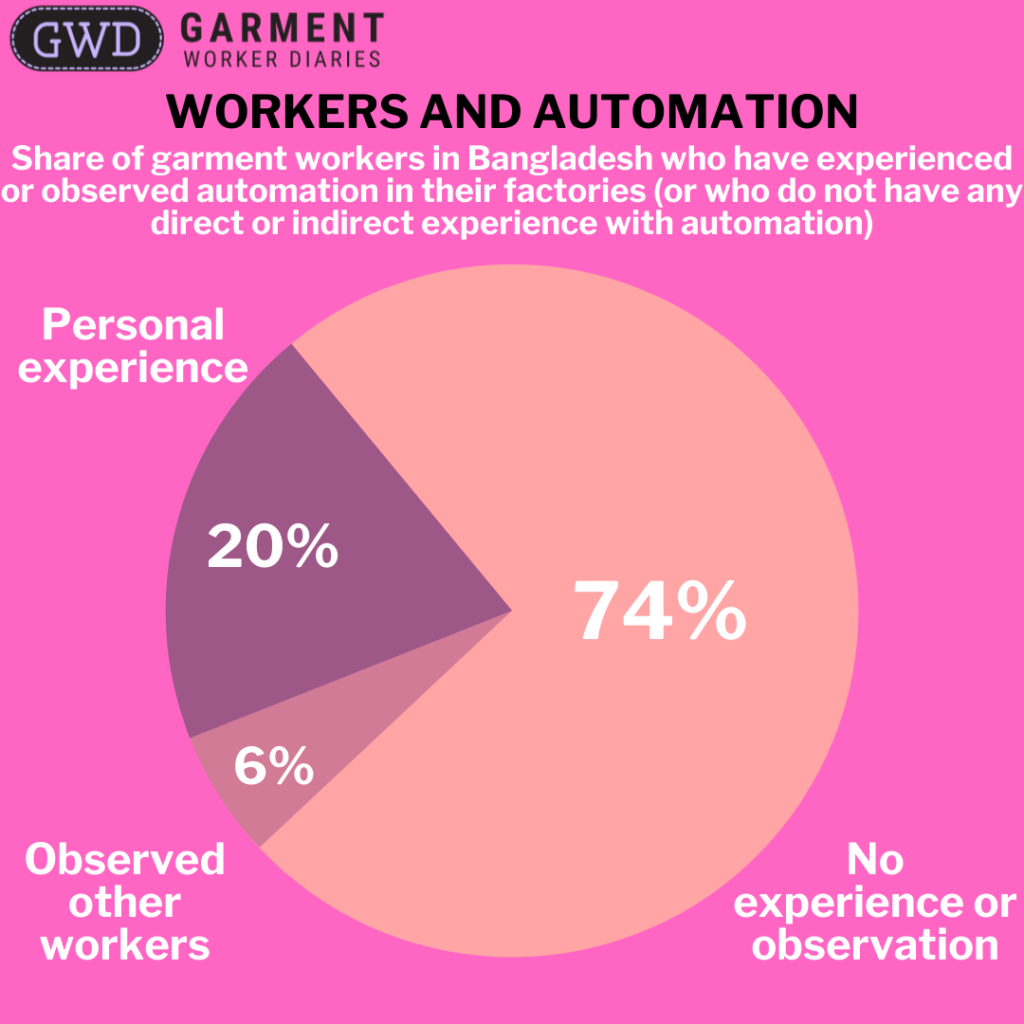

About one quarter of workers (26%) had either experienced automation or observed colleagues experiencing it.

Our survey then dug into the experiences of workers who had experienced automation themselves—a sub-sample of 215 workers of whom 169 (79%) are women and 46 are men. We looked at the data on a gender disaggregated basis and saw few differences between men and women in their responses. With this in mind, we will be reporting results for both men and women, to take advantage of the full sub-sample.

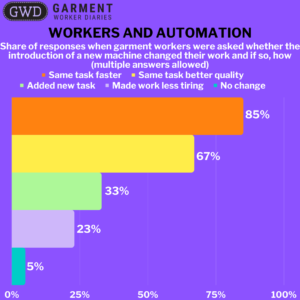

We asked workers whether the new machine changed how they worked and included a list of options that they could choose from, allowing them to choose multiple options. The most common response from workers was that the new machine allowed them to do the same task more quickly (85% of workers selected this option). The second most common response was that the new machine allowed them to perform the same task but with better quality outcomes (67% of workers). The third most popular option—that the new machine enabled the worker to add a new task to their work–garnered one third of workers’ votes. These responses suggest that, at this time, the introduction of automation in Bangladeshi factories is predominantly automating existing tasks to increase productivity and quality, but there is some evidence that new machines have “disrupted” the way apparel items are manufactured by adding new tasks for workers to do, not simply automating existing tasks.

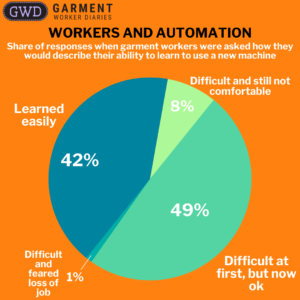

An important theme in the debate about the impact of automation on workers is the extent to which workers are able to learn how to use the new machines that are coming online. We asked workers who had experience with automation this question directly:

How would you describe your ability to learn how to use the new machine?

Almost half said they learned how to use the new machine easily, and 42% said they had difficulty at first but are now “ok”. This is not necessarily surprising given that the new machines the workers were given were largely automating existing tasks.

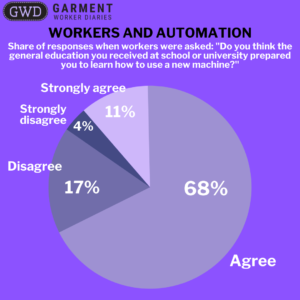

We also wanted to know from workers whether they felt prepared for automation, given the experiences they had had:

Do you think the general education you received at school or university prepared you to learn how to use a new machine?

Over three-quarters (79%) of the workers asked this question agreed or strongly agreed that their general education had prepared them to learn how to use a new machine. This confidence in their ability to learn how to use a new machine is likely colored by the fact that they did not, generally, have a disruptive automation experience.

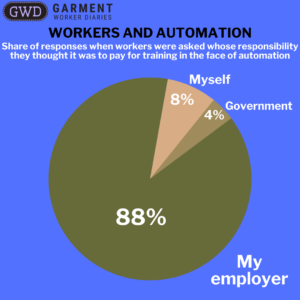

Last in our series of questions about workers’ preparedness for automation, we asked them:

Whose responsibility is it to pay for the education and training necessary for you to stay employed at your current or a new workplace in the face of the introduction of new machines?

Overwhelmingly, workers see this as the responsibility of their employer.

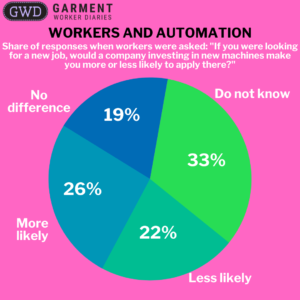

Finally, to get a sense of workers’ general attitude towards automation we asked them:

If you were looking for a new job, would a company investing in new machines make you more or less likely to apply there?

A third of workers did not know how to answer this question, while another fifth stated that the company’s behavior would make no difference. Of the remaining half who expressed an opinion, there was an almost even split between those saying that they would be more likely to seek employment with a company investing in new machines and those saying they would be less likely to do so.

Conclusion

While not a great deal of garment workers in our study sample reported experience with automation, their experiences have mainly been positive. If we assume that the rest of the workers would report similar results upon encountering automation, this goes a long way to suggest that garment workers in Bangladesh are open to the introduction of new machines and that not only do they feel capable of learning how to operate new machines, they do learn how to operate them, even if it takes some workers a bit longer. The one caveat to this positive conclusion is that much of the automation workers have experienced has simply been the automation of existing tasks, not the disruption of their work and a whole new way of doing things. This is likely to be the nature of automation in the future, and it is unclear how well prepared workers are for a more disruptive type of automation.

The data used for the analysis presented here come from interviews conducted over the phone in early April 2022 with 1,281 workers. Of the full sample of workers, 215 had experienced automation either personally or through observation. 169 (79%) of those workers were women and 46 were men. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.