This week’s Garment Worker Diaries blog has been guest-written by the South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM), our partner in the field in Bangladesh. MFO and SANEM have been working together for over four years now and SANEM was instrumental in helping to scale the GWD project to its current full capacity in Bangladesh. MFO is pleased to present this blog about the educational status of children living with garment workers in Bangladesh and how their education might have been affected during the COVID-19 pandemic. The blog’s data are drawn from questions SANEM recently posed to GWD respondents during the weekly interviews. We are also publishing the full blog in Bangla which you can find directly adjacent to this blog post on our Worker Diaries homepage.

***

The lockdowns and school closures during COVID-19 affected 36.5 million students in Bangladesh. These had far-reaching impacts such as learning loss, school dropouts, and even child labor or child marriage. According to UNESCO, remote learning cannot fully compensate for the lack of face-to-face education. Moreover, the existing digital divide made the inequality in access to education more visible during the pandemic.

In January 2022, 1,280 garment workers were surveyed regarding the education of children in their households as a part of the Garment Worker Diaries (GWD) project. Just over half (56%) of the garment workers participating in the project have one or more children under the age of 19 living in their household. The survey explored the challenges faced by these children during the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic situation. It also tried to dig into the issue of impact on education further by asking the respondents about their children’s access to online classes, inconveniences faced to attend the classes, the effectiveness of online classes, and the recovery of lost learning opportunities.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Bangladesh; numbers in graphs may not sum to 100% due to rounding.

Learning Loss

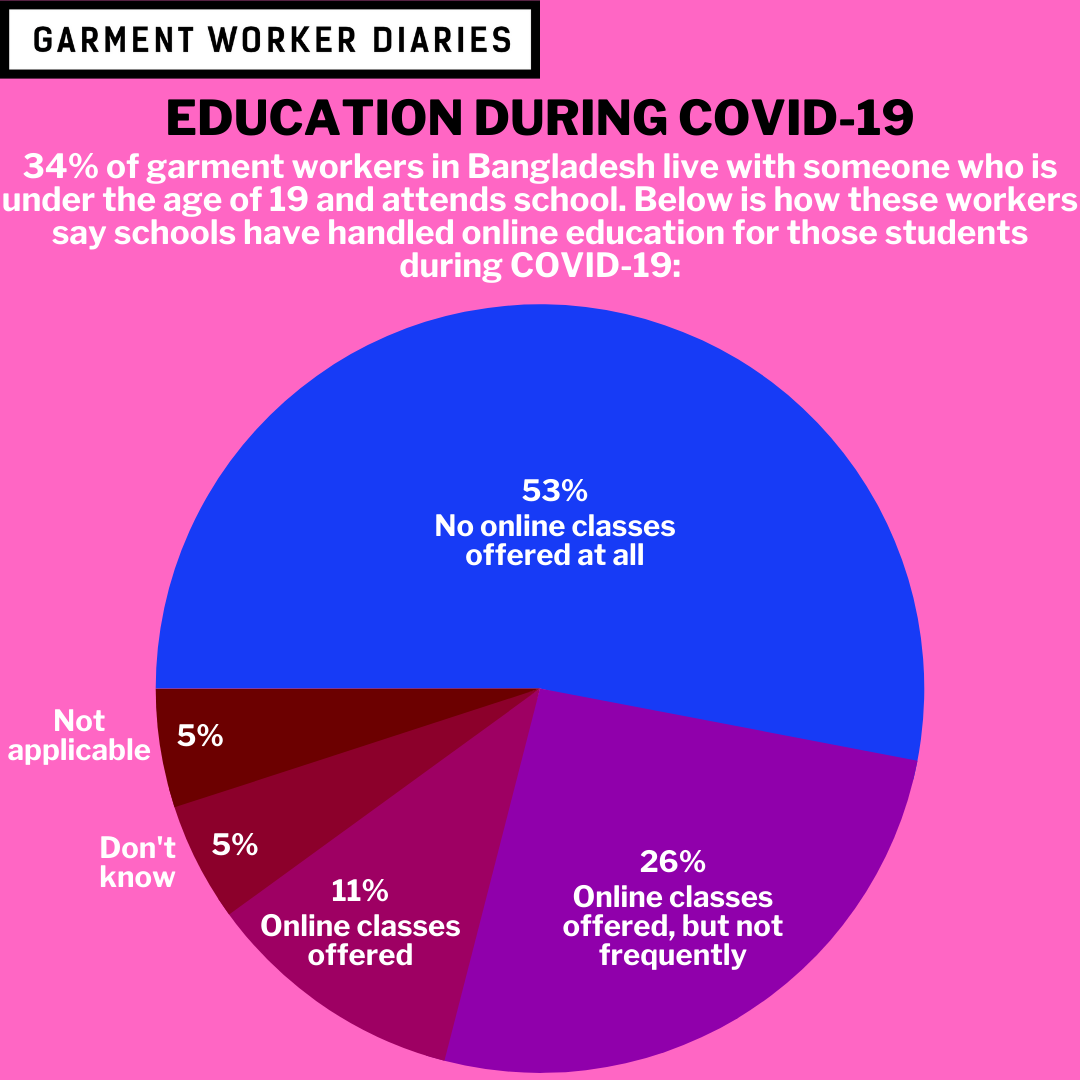

In the face of their inability to conduct in-person classes during the pandemic in Bangladesh, many schools and educational institutes arranged online classes through Apps/Software of online meeting services or distance learning opportunities through social media (Facebook/YouTube). Among garment workers with one or more children 19 or younger living at home, about 61% have at least one school-going child. Among households having school-going children, 11% reported that the school gives regular online classes, 26% give online classes but not frequently, and more than half of the households (53%) responded that the school does not give online classes at all. The figures make it clear that not all the schools have a similar capacity to arrange online classes.

The survey responses gave a clear indication of the fact that lower-income households with limited access to the internet, devices, and other facilities found it very hard to attend these classes and thus lagged behind. Even if the school takes online classes, only 9% of the students in the respondent households having school-going children attend online classes regularly, 21% do attend but not frequently, and 60% do not attend at all. The students of the respondent households faced various inconveniences in attending online classes including not having access to any device (15%), not having sufficient internet network facility (14%), not having a sufficient device (11%), unable to bear the cost of the internet (10%), not mentally prepared for online classes (10%), and not being accustomed to technology (10%). Almost all respondents (94%) reported having to pay for internet service required for education themselves.

Furthermore, the quality of the online classes is low. In the survey, 31% of respondents with children attending online classes described those classes as either not at all effective or ineffective. Only 18% found it effective or very effective and the other half of the respondents (52%) expressed uncertainty about the effectiveness.

Alternatives to online classes

The survey responses give a strong indication of the value garment workers put on the education of their children. In the face of problems getting access to quality education through schools, parents taught their children at home, the child willingly self-studied by themselves at home, the parents hired private tutors, elder siblings helped with their studies. These are the strategies workers reported that they are applying to recover the learning losses during COVID-19. However, according to the respondents, 24% of boys and 21% of girls have not yet recovered from their learning losses.

Drop outs

To get an idea about the school dropout rate, the survey asked the garment workers if their children will continue their studies when the school reopens after COVID-19. Alarmingly, 9% of the households having school-going children reported that either some of their children or all of them will not continue their studies after COVID-19. The causes of dropouts include the fact that they are unable to bear the cost any more or the children got involved in economic activities during COVID-19 and are not in a position to return to their studies after COVID-19.

Even disregarding the COVID-19 situation, the number of expected years of education is already lower in girls compared to that of boys in garment worker households. While 89% of households with boys expected them to at least gain their higher secondary school certificate, only 77% of households with girls expected them to do so. Interestingly, parental expectations for girls and boys reaching post-graduate education are the same: 37% of boys are expected to reach that level, while 35% of girls are.

Faith in the government response

The government has a huge role during the COVID-19 situation to take necessary measures in the education sector to mitigate the learning losses, dropout rate, and other far-reaching impacts on the education of children. However, 19% of the respondents think that the measures taken by the government are insufficient, only 8% reported them to be sufficient.

Child care provision

As children remain at home at the time of school closure, taking care of the children can be very difficult in the absence of daycare at the workplace or supportive family members at the household. Almost 62% of the workers reported that their employer does not have any childcare facility available, and a further 21% of respondents is uncertain about whether this is the case or not. In factories where childcare facilities are available, the factory bears the cost in 88% of cases. In the absence of factory-based day-care, grandparents take care of the children when the garment worker is at work (31% of the time), community-members or neighbors take care in 19% cases. In 12% of households with children under the age of 14, there is nobody to take care of the children when the parents are at work.

The survey was conducted between 13th January and 23rd January 2022 by South Asian Network on Economic Modeling (SANEM) in collaboration with Microfinance Opportunities (MFO). Among the 1,280 surveyed respondents, 76% (975) workers were female and 24% (305) workers were male. About 56% of the respondents have at least one child under the age of 19 in their house, 33% have one child and 22% have 2 to 3 children. Around 58% of the respondents have one or more girl children, 64% have boy(s). Of these, households with children under 19, almost all (90%) have one or more children under the age of 14. The expenditure on education in these households ranged between Tk. 1,000 and Tk. 5,000 in the month preceding the survey.