In the Spring of last year, just like many other people around the world, garment workers in Bangladesh confronted a COVID-19 pandemic threatening the stability of their livelihoods. Many garment producing-factories did end up pausing operations as apparel orders briefly plummeted or were halted by brands. Fortunately, the Bangladeshi government stepped in to offer crucial monetary assistance, paid out to the workers as factory wages. But unlike many other people around the world who were also receiving direct government benefits last year, this would have been the first time the majority of garment workers in Bangladesh received a digital wage payment.

For our first blog of 2021 we’d like to reflect on two pillars of the infrastructure framing garment workers’ digital lives: businesses and government. We’ll first look at the onboarding phase of the digital experience, with special attention paid to how workers feel their factory management handled the shift to digital; and then we’ll look at the government’s perceived role in providing a social safety net.

Factory Management’s Role in Digital Transitions

When it comes to trusting their factories, a majority of garment workers agree that receiving digital wage payments via mobile financial services (MFS) inspires more confidence in the worker-factory relationship than does being paid in cash:

- 61% of workers agreed with the phrase “I can trust my factory management more if they pay me via MFS”

- 62% of workers agreed with the phrase “I know I will receive all my dues if the factory pays me via MFS”

Communication from factory management often represents the first step in the pivot towards digitization that workers will experience. We asked workers whether or not they felt they received sufficient support and training from their factory management during the digitization process. What they told us shows mixed feelings:

- 54% of workers agreed with the statement “We received sufficient training and support for using MFS by factories”

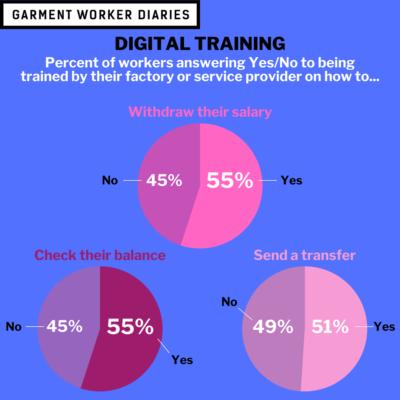

When it comes to receiving training on performing specific types of digital transactions, workers’ feelings were also mixed:

- 55% of workers who underwent wage digitization said they received training from either their factory or service provider on how to check their balance and how to withdraw their salary

- 51% said the same thing about receiving training to perform digital transfers using their new bank or mobile money account

Workers also displayed ambivalent feelings of preparedness when reflecting upon their first digital payments. While 67% of workers said they had sufficient time to open their digital account to receive their first digital salary payment, 45% also said they had to open the account in such a hurry that they didn’t have time to fully understand the new service.

Perception of Government

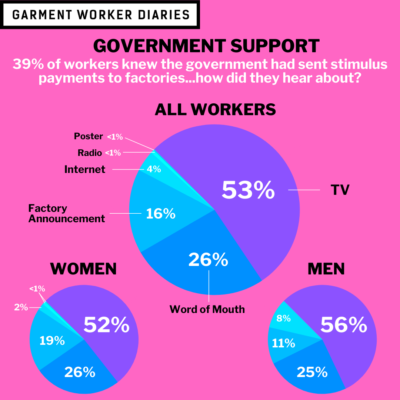

Many garment workers in Bangladesh received a pay check in May of last year, but in many of these cases it wasn’t factories footing the bill. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic shutting down factory production in April 2020, the Bangladeshi government had decided to use factories as a funnel to pay workers emergency relief funds to help avert a payroll crisis. However, only 21% of garment workers are aware that they received some kind of government funding last year. This is despite the fact that 39% of workers say they’ve heard of stimulus packages for ready-made garment factories that the government has given out. Only 16% of those workers who knew of the stimulus packages heard about it from their factories: 53% heard about the stimulus from TV and the rest by word-of-mouth or other media.

This suggests that factories could be a doing a better job communicating to workers that many of them did indeed receive some government assistance, and that this was the reason for the massive shift to digital wage payments from April to May last year. As it stands, 32% of workers said they were not given any reason for the shift to digital wages.

If garment workers were aware of social safety nets, it might improve their perception of the government’s role in handling crises. To gauge that trust in the government, we asked garment workers how certain they felt that they would receive some kind of governmental support if they lost their job. A full 76% of workers said they were not confident they would receive any support, with 22% saying they weren’t sure. This left just 3% of garment workers with faith in the government to support them in time of need.

The data presented here come from two sets of interviews conducted over the phone with two pools of 1,275 workers and 1,283 workers. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.