Garment workers in Bangladesh do not want their children to grow up to become garment workers. Instead, they want their children to get educated. That is the overwhelming sentiment expressed this past October when we asked workers if they wanted their children to follow in their footsteps (see our #Opendiaries post). As one worker told us:

“I didn’t want that because I want my children educated well and not to lead a life like me. They have to survive their life with much less pain or problems than I face. They need to lead a happy life like I want.” – 38 year-old male garment worker in the industry for eight years

Overall, 96% of garment workers surveyed said they did not want their children to become garment workers. In another survey a couple months later involving a very similar pool of respondents, we also learned that 71% of garment workers found no joy in their work.

Needless to say, this does not bode well for any long-term self-actualization possibilities the garment industry has to offer. However, none of this has deterred garment workers from wanting to give their children a better future, or from valuing education. And it hasn’t deterred many garment workers themselves from wanting to become better educated.

This is the first of two blogs, in which we present the results from a recent survey MFO and SANEM conducted asking respondents to share their attitudes towards secondary and higher education. In this blog we focus on workers’ educational aspirations for their children. In the next blog, we will look at workers’ educational aspirations for themselves.

Notes: Numbers in graphs may not sum to 100% due to rounding; banner photo of children’s school books courtesy of a garment worker.

How High Should the Children Go?

Overall, 45% of the garment workers to whom we presented this education survey reported having a female child, and 44% reported having a male child. Those without a girl or a boy were excluded from the analysis below.

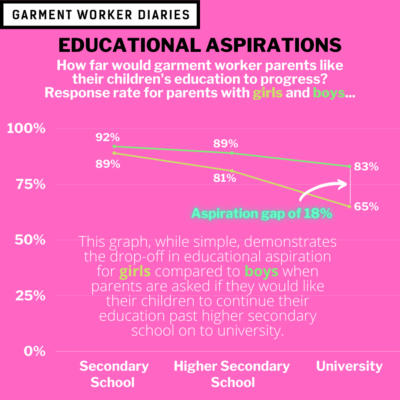

There was little difference among those respondents with female children and those respondents with male children regarding how far they would like their children’s education to advance at the secondary school level. But a disparity in support for furthering their child’s education came at the university stage, when a somewhat lower share of parents with girls reported that they’d like their child to attend university, compared to parents with boys. Nevertheless, the general impression coming out of the workers’ answers is that the vast majority of parents of both girls and boys want their children to go to school, for as long as they can.

We presented the survey to respondents in the form of a decision tree: if a parent said that they did not want their child to complete secondary school, then they were not presented with the next question, which asked if they wanted their children to complete higher secondary school, and so on. Below is a chart representing the proportionate response rate of parents who would like their child to attain the indicated education level, based on how many parents made it to that stage in the decision tree process. The “cumulative” row shows the share of “Yes” at each stage for all parents of children, not just those who aspire for their children to reach that stage:

|

Would you like your child to get a Secondary School Certificate? |

[Then] would you like your child to get a Higher Secondary Certificate? |

[Then] would you like your child to attend University? |

||||

|

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

Girls |

Boys |

|

|

Yes |

89% |

92% |

92% |

96% |

79% |

93% |

|

Cumulative |

89% |

92% |

81% |

89% |

65% |

83% |

In other words, cumulatively, about 90% of parents want both girls and boys to get a Secondary School education, 81% of parents of girls and 89% of parents of boys want them to get a Higher Secondary Certificate, but 65% want their girls to attend university, while 83% want their boys to do so, suggesting a growing gender-aspiration gap the higher up the education ladder their children climb. These data also suggest a huge university-level aspiration-reality gap, because only 17% of young women attend university in Bangladesh today and only 24% of young men do so, according to the World Economic Forum’s latest Global Gender Gap Report.

Value of a University Education

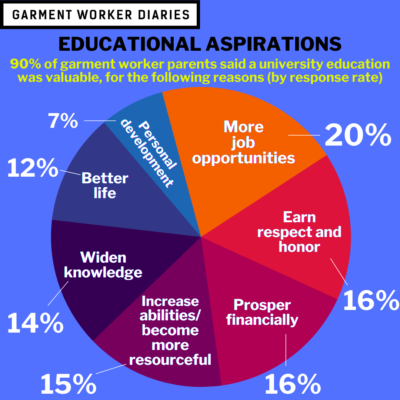

We also wanted to get a sense of the value workers put on education. The vast majority, 90%, of respondents answered “YES” to the question “Do you believe that attending university gives a person new opportunities for work and personal wellbeing?” (nearly identical rates for women and men). Digging into these responses a little further we found that the most frequently given reason in support of a university education was that it confers more job opportunities. That wasn’t the only value parents recognized in attending university, however. Below is the full range of their answers sorted by frequency of response (these are overall numbers, as women and men’s response rates were very similar):

|

Reason Attending University is Valuable |

Response Rate |

|

More job opportunities |

20% |

|

Earn respect and honor |

16% |

|

Prosper financially |

16% |

|

Increase abilities and/or become more resourceful |

15% |

|

Widen knowledge |

14% |

|

Better life |

12% |

|

Personal development |

7% |

|

Other |

0% |

Barriers to Getting a University Education

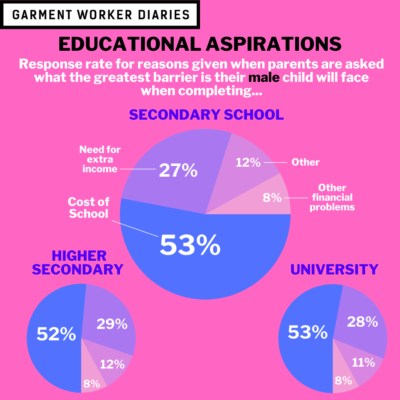

Finally, we asked parents about the barriers they face in helping their children get a university education. All the barriers that could impede their child’s progress were financial in nature (besides a small percentage answering “Other”). Not one parent responded by telling us that a family problem, an unsafe school environment, a male family member refusing consent, not having enough time, or getting married could hinder their child’s educational progress. It seems the only thing standing in their way is money.

All data presented here come from interviews conducted over the phone with a pool of 1,280 workers. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.