In our blog last month which brought the Garment Worker Diaries study up to speed through November 2020, we discussed the possibility that the garment sector in Bangladesh might again require government assistance to weather the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the resultant international downturn in garment orders.

What the data through the end of December 2020 are telling us is that garment workers in Bangladesh worked more in December than any month since pandemic precautions began in earnest. And among constants such as lower median salaries for women despite similar amounts of hours worked compared to men, there are positive trends to report, such as increasingly higher rates of food security and lower rates of illness. These results are for our sample as a whole, but the results may vary across factories. In the coming weeks, we’ll take a hard look at the data to see if there are any discernible differences between 1st tier and 2nd/3rd tier supplier factories. For now, let’s dig into the particulars for the full sample from across Bangladesh.

Note: Banner photo courtesy of a garment worker in Narayanganj

Employment

As noted above, garment workers in Bangladesh worked more hours in December than in any month since April, when we re-launched the study in order to document the COVID-19 crisis. 87% of the respondents in our study told us they worked in December, and the median hours worked was 259 (257 for women and 260 for men).

Among the 13% of respondents who did not work in December, factory closures and layoffs accounted for the same proportion of unemployment reasons as in November, both at 9%. What all of this would indicate so far is that if a downturn is coming to the garment sector, it had not yet struck as of the end of last year.

However, the stimulus loans the government provided to garment factories earlier in 2020 must be repaid, with a service fee, and there have by now been some reports (here and here) that lower than usual garment orders are making repayment of these stimulus loans difficult for factory owners. So we’ll have to wait until the end of January to see if the workers in our study start reporting harsher economic realities on the ground.

Salary Payments

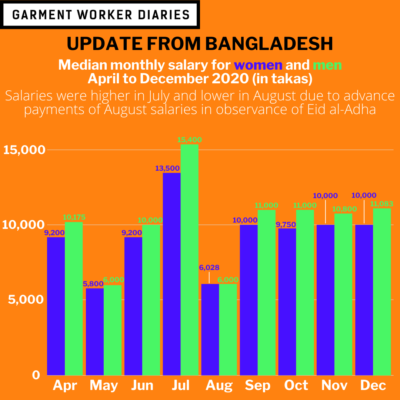

In December, 85% of all garment workers in our study received a salary payment (83% of women and 89% of men). The median amount for a salary payment was Tk. 10,300 (Tk. 10,000 for women and Tk. 11,083 for men). Garment workers are generally paid for the work performed during the previous month, as a result the salary payment received in December was for work performed in November.

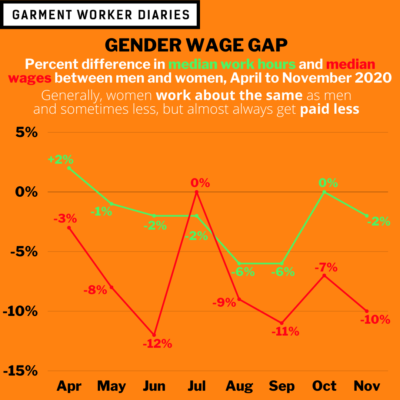

As the chart below demonstrates, this last payment represented yet another time in which the median work hours for women was slightly different from that of men, but the median salary for women was disproportionately lower considering the amount of hours they worked. In two months, April and October, women actually worked one median hour more than men, but got paid 3% and 7% less, respectively.

|

|

Median Work Hours |

Median Salary (in Tk.) |

||||

|

Month |

Women |

Men |

% Difference |

Women |

Men |

% Difference |

|

April |

42.5 |

41.5 |

2% |

5,800 |

6,000 |

-3% |

|

May |

174 |

176 |

-1% |

9,200 |

10,000 |

-8% |

|

June |

246 |

252 |

-2% |

13,500 |

15,400 |

-12% |

|

July |

254 |

258 |

-2% |

6,028 |

6,000 |

0% |

|

August |

198 |

210 |

-6% |

10,000 |

11,000 |

-9% |

|

September |

240 |

255 |

-6% |

9,750 |

11,000 |

-11% |

|

October |

241 |

240 |

0% |

10,000 |

10,800 |

-7% |

|

November |

254 |

260 |

-2% |

10,000 |

11,083 |

-10% |

These numbers show an interesting gender/pay dynamic and more in-depth analysis is required to better understand what the root cause is and what is driving this gap. To this end, MFO and SANEM will be performing a detailed analysis on this issue, taking into account other indicators such as skill level, education, seniority within the factory and years in the garment sector. We’ll also take a hard look at the data to see if there are any discernible differences between 1st tier and 2nd/3rd tier supplier factories.

Digital Payments and Financial Transactions

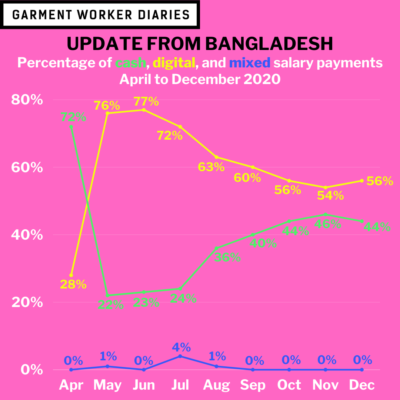

One trend did reverse itself in December, which was the month-over-month declining digital salary rate: in November, 54% of salary payments were digital, which ticked up slightly to 56% in December. Other financial transactions (intra-household transfers, loans, remittances, savings, withdrawals, medical payments) were conducted digitally in December at about the same rate as in November, which is to say that cash still forms the basis of almost all financial transactions. One exception is remittances that garment workers send to friends, family and other people in their networks: 54% of those kinds of transactions in December were digital.

Food Security and Health

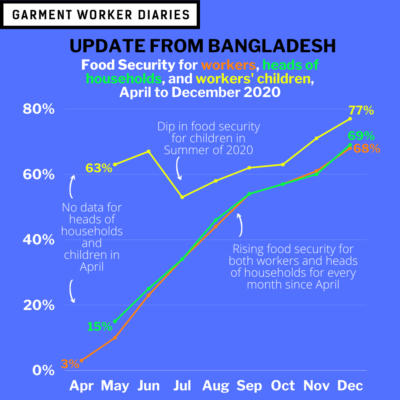

In December, 32% of workers said they weren’t eating enough, 31% of workers said the head of their household wasn’t eating enough, and 23% of applicable parents said their children were not eating enough. Despite those numbers sounding fairly high, these are the best food security rates yet since we started keeping track in April. Using food security as a proxy for resilience during adversity, garment workers have faced the global pandemic and been able to improve their situation for eight straight months in a row (there was a dip in children’s food security during the Summer, but that trend did not last and children ended up more food secure in December than when we began surveying workers about their children’s food security in May).

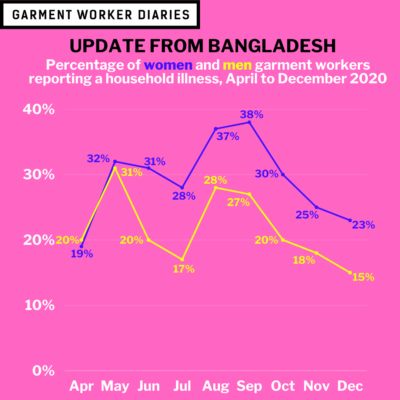

The illness rate also fell to one of its lowest levels all year, with 21% of respondents reporting a household illness in December. This is only two percentage points higher than in April at the onset of the COVID-19 outbreak. Only seven respondents, representing 3% of those reporting illness, said they did not seek medical attention for their household illness, and the only two reasons given for not seeking help were not having enough time and medicine already available in the home. All of this suggests that garment workers ended the year on an upward health trajectory, perhaps not better off than how they began the year, but better off than during the worst of what 2020 had to offer.

The data are drawn from interviews with about 1,300 workers interviewed weekly from April 2020 to December 2020. The number of worker responses in a particular month vary depending on interview participation rates throughout the month, but were never below 1,206 during this period. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.