A few weeks ago we published a blog about garment workers’ attitudes towards and preferences for digital or cash payments. We’re continuing that theme today by taking a look at a few other aspects of garment workers’ digital experiences in Bangladesh, including workers’ general feelings of empowerment and customer satisfaction, with a focus on gender differences.

Note: some data discussed in this blog and depicted in the graphics are derived from survey questions with which respondents could agree, disagree, strongly agree, strongly disagree, or neither agree nor disagree (or select that the prompt was not applicable to them). Because most respondents selected either “agree” or “disagree”, we will conflate “strongly agree” and “strongly disagree” with “agree” and “disagree”, respectively, unless otherwise specified. Numbers may not sum to 100 due to rounding.

Women’s Digital Empowerment

As we shared in our blog on payment preferences a few weeks ago, women garment workers are a bit less likely than men to view digital payments in a positive light. Let’s continue unpacking some more of these attitudes.

Digital Inclusion

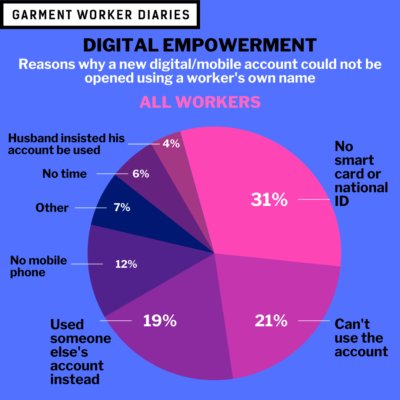

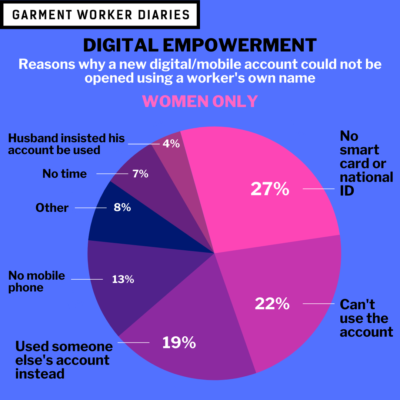

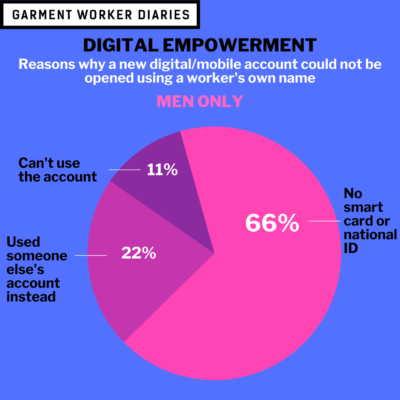

A large majority of garment workers whose wages were digitized (87%) have been able to open their new bank or mobile money account in their own name. There is an important gender disparity here, however, as 17% of women reported that their new account was not in their own name compared to just 5% of men who said the same.

The most frequent answer given by those respondents who couldn’t put their own name on their account was that they did not have a smart card or national ID. However, women reported at double the rate of men that the reason they couldn’t put their own name on their account was that they didn’t know how to use the account. And only women reported the complete lack of a mobile phone as the reason they couldn’t register their account in their own name…not one man in our study seemed to have this problem.

And among those 17% of women who couldn’t put their own name on their account, a large minority, 41%, agreed with the statement “If I was the man of the house I would have gotten my own wallet”.

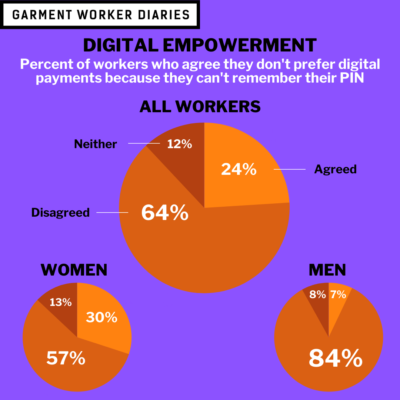

Women might also be receiving less training in digital skills building, as agreement with the phrase “I don’t prefer getting paid in mobile financial services (MFS) because I can’t remember my PIN” hints at: 30% of women agreed with the phrase compared to just 7% of men.

We did receive some encouraging reports about actual cash withdrawal trips: only 31% of women agreed with the phrase “I feel uncomfortable going to mobile agent” and only 28% agreed with the phrase “My husband does not want me to visit the mobile agent”. And among both women and men workers, 81% agreed that there are ample mobile money agents in their neighborhood.

Digital Satisfaction

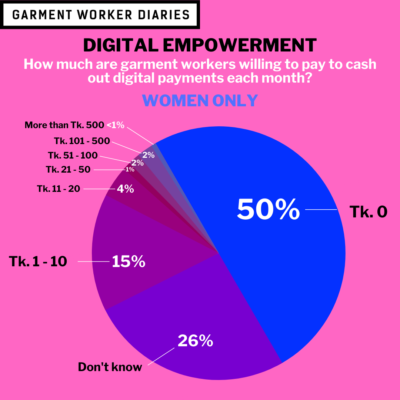

When asked how much they were willing to pay to cash out a digital payment per month, 51% of workers said they were willing to pay exactly nothing. Only 11% of workers said they were willing to pay even 11 Taka or more (the equivalent of about 13 cents in US Dollars). In all, 44% of workers agreed with the phrase “I don’t prefer getting paid in MFS because the cash out charge is high”. Women were less satisfied with the service charge than men, as 47% of women agreed with the statement compared to 33% of men.

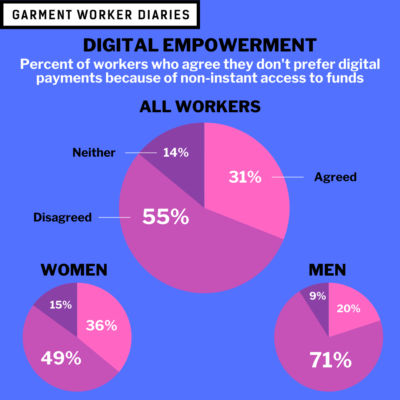

In-depth interviews we conducted last year with garment workers whose wages were digitized revealed that one of the biggest concerns among women was that digital payments meant less access to cash. This still seems to be the case for more women than men: 36% of women agreed with the phrase “I don’t prefer getting paid in MFS because I don’t have instant access to funds” compared to just 20% of men.

In all, only 26% of workers disagreed with the statement “I feel empowered being able to use a MFS wallet”. Just under 50% agreed with the statement, and the rest didn’t feel one way or the other. Although, when segmented by gender, 47% of women agreed that they felt empowered compared to 57% of men.

The data presented here come from interviews conducted over the phone with a pool of 1,275 workers. These workers are employed in factories spread across the five main industrial areas of Bangladesh (Chittagong, Dhaka City, Gazipur, Narayanganj, and Savar). Just over three-quarters of the working respondents are women, roughly representative of workers in the sector as a whole.