The Garment Worker Diaries is a multi-year project led by Microfinance Opportunities is collecting regular, credible data on the work hours, income, expenses, and financial tool use of workers in the global apparel and textile supply chain in producing countries. The objective of the project is to have the data inform: government policy decisions, collective bargaining, and factory and brand initiatives related to improving the lives of garment workers.

The project began in 2016 when MFO, in collaboration with local research firms in Bangladesh, India and Cambodia, collected data from 180 women in each country every week for a period of a year. We are now entering the second phase of the project in which we are scaling up our efforts, first in Bangladesh and later in 2019 in Cambodia. Our goal is to be collecting and disseminating Diaries data in five producing countries by 2021. The data will result in a major improvement in the transparency of global supply chains.

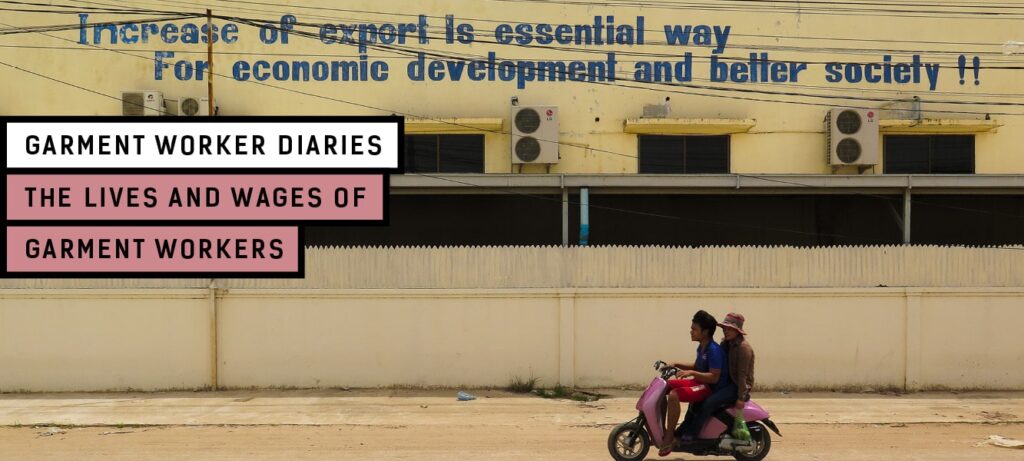

Dozens of beige colored garment factories line the streets on the outskirts of Phnom Penh. Ten-foot high walls, metal gates, and security checkpoints at the entrances guard the compounds. Early in the morning, garment workers who live nearby leave their homes—often a 70 square foot room with an accompanying toilet—and enter these factories by the thousands to begin their workday. For the next eight to 12 hours, they cut and sew clothes for major clothing labels, who sell the finished products to you and billions of other people across the globe. When the workers emerge, many complain of headaches and chronic pain in their arms and backs, aggravated by the repetitive motions of their work. They perform this routine six days a week, and for their work, the government of Cambodia mandates that factory owners pay them a minimum of $140 per month, or seventy cents an hour based on a 50-hour workweek. The situations in Bangladesh and India are similar. Hundreds of thousands of workers labor long hours in the hope of receiving the minimum wage, which is set at $68 and $105 per month respectively.

Labor rights advocates say that workers in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India often receive less than the minimum wage. Even if they do receive the minimum wage, the advocates say, it may not be enough for workers who need to pay housing costs and provide themselves and their families with food, health care, and other necessities.

If their wages cannot cover their necessities, how do they survive? Where do they get the money to cover basic expenditures? Do they choose between sending money to their families in rural villages and buying enough food to feed themselves for the week?

What goes on behind those big, metal gates? Do their supervisors encourage or berate them when a major clothing order is due? How frequently do they experience chronic pain from their work? What do they do when they are injured?

In the first phase of the project we oversaw field researchers who asked these questions to 180 garment workers per country in Bangladesh, Cambodia, and India. During the 12 months of the study from July/August 2016 to July/August 2017, interviewers visited the same set of garment workers each week to learn the intimate details of their lives. They asked the garment workers about what they earned and bought, how they spent their time each day, and whether they experienced any harassment, injuries, or suffered from pain while at the factory. The interviewers learned about important events that happened in the workers’ lives too—from birthday parties and weddings to illnesses and funerals for family members and friends. In the second phase, we have scaled up the number of workers we are reaching to 1,300 workers in Bangladesh. You can find out more about the second phase here and on our data portal.

This data is a treasure trove—imagine what you would learn about a person by asking her detailed questions about her life each week, every week, for an entire year. Our job as researchers is to analyze it objectively and provide answers to the questions of what happens behind those factory gates and, more importantly, what happens after the workers leave them.

Our hope is that clothing companies, consumers, factory owners, and policy makers will be able to use the insights we identify to understand how the decisions they make affect garment workers’ condition. To this end, we are working with Fashion Revolution to get our data in front of change-makers who can influence the global clothing supply chain, the regulatory environment, and the social protections available to garment workers.

One of the most important agents of change is you—the consumer, the driver of trends and clothing orders. Over the course of the next several months, Fashion Revolution and our team will share findings from our project via social media, blogs, fanzines, reports, and exhibitions. We encourage you to stay informed of our work so that you too can be an advocate for the people who made your clothes.

Author: Guy Stuart, Microfinance Opportunities

C&A Foundation is providing financial support for the Garment Worker Diaries. We are collaborating with Fashion Revolution to distribute the results. Our local partners in the first phase were BRAC (Bangladesh), TNS (Cambodia), and Morsel Ltd. (India). In the second phase, we are collaborating with SANEM, a Bangladesh research organization, and Bangladesh Country Office of SNV Netherlands Development Organisation. In addition to the on-going support of C&A Foundation, we are receiving support from the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Dhaka.